17min reading time

Disclaimer:

This Insight article was created in collaboration with yabeo.

Why supply chains must become more transparent and sustainable

The hype around ESG transparency within a company has been great in recent years – from Greenly (carbon tracking) to PlanA and Planetly (ESG reporting), there has hardly been a month without new start-ups or funding rounds being announced.

But how does it actually look like outside of companies, i.e. in their supply chains? Oranges from Spain, coffee from Colombia or fast fashion from Asia – global trade is booming, but supply chains are conceivably intransparent. While global trade has brought a lot of prosperity on the one hand, the ecological and social consequences have been pushed into the background. This refers to poor working conditions on site and the destruction of the environment through chemicals, waste and CO2 emissions.

25 million people worldwide are victims of forced labor and wages below subsistence level are not unusual. They threaten the livelihood of many people. In 2022, for example, 734 million people still have to live with less than $1.90 a day. Many people work under life-threatening safety standards and suffer lifelong health consequences. The International Labor Organization reveals that a large percentage of the world’s 170 million child laborers are forced to make textiles and clothing to meet consumer demand in Europe and the U.S., and do so under inhumane working conditions. Unprotected contact with chemicals, no days off and hardly any breaks are the norm here.

The exploitation of nature, environmental pollution and destruction are also part of global supply chains. For example, supply chain greenhouse gas emissions are on average 11.4 times higher than internal emissions, or about 92% of a company’s total greenhouse gas emissions.

These problems are putting increasing pressure on companies to change and take a closer look at economic practices in their supply chains. On the one hand, the demand comes from the customer side. Detailed information about a product’s sustainability increases the likelihood of a purchase decision for seven out of ten respondents, and a study conducted by EY confirms that 66% of consumers in Germany are willing to spend more money on sustainable alternatives.

And policymakers are also responding to the challenges. For example, legislatures in Europe have recently passed a number of different initiatives and laws requiring companies to take responsibility for economic practices in their supply chain. Complying with these is complicated and is driving demand for software that simplifies reporting and due diligence, saving time and money.

We take a closer look at these regulatory and societal developments in this article, and examine technologies that are helping companies quantify and reduce the environmental and social footprint in their supply chains. While technology has already helped solve many problems, we conclude by sharing our perspective on the areas that still need more innovation to meet the challenges of global supply chains.

What the world community & Germany have done so far

As early as 2011, the UN took the first steps toward mitigation, particularly on the issue of human rights violations. Consequently, the UN adopted the Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights, which call on partner states and their companies to protect and respect human rights and to take remedial action in the event of violations. However, the Guiding Principles do not constitute legally binding guidelines; they are to be understood merely as a consensus between the community of states, business and civil society.

Despite their voluntary nature, the UN guidelines have triggered changes at the national level. For example, in 2016, Germany adopted an action plan to flesh out the guiding principles and meet the social goals of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. The action plan was intended to ensure that, despite the voluntary nature of the implementation of the Guiding Principles, at least 50% of all German-based companies with more than 500 employees would apply the core elements of human rights due diligence and integrate corresponding measures into their corporate processes by 2020. However, this target was missed. A review ordered by the German government in October 2020 revealed that only 13-17% of all companies concerned complied with the requirements.

The reasons for this are obvious: profitability and cost pressure continue to take precedence over voluntary ethical principles.

The new supply chain act in Germany and other european initiatives

Due to the low level of implementation and increasing social pressure for more transparent supply chains, the Supply Chain Due Diligence Act, or LkSG for short, was passed in June 2021. The aim of this law is the mandatory monitoring of compliance with minimum standards in the supply chain. The LkSG will take effect from January 2023 and will gradually affect around 4,800 companies in Germany directly.

Questions that affected companies will therefore have to deal with from next year include:

- How ethically and sustainably do companies in my supply chain operate?

- Are my business partners involved in child labor or forced labor outside Germany?

- How sustainable is the handling of recyclables and waste? Have I established detailed, fair and transparent occupational health and safety measures?

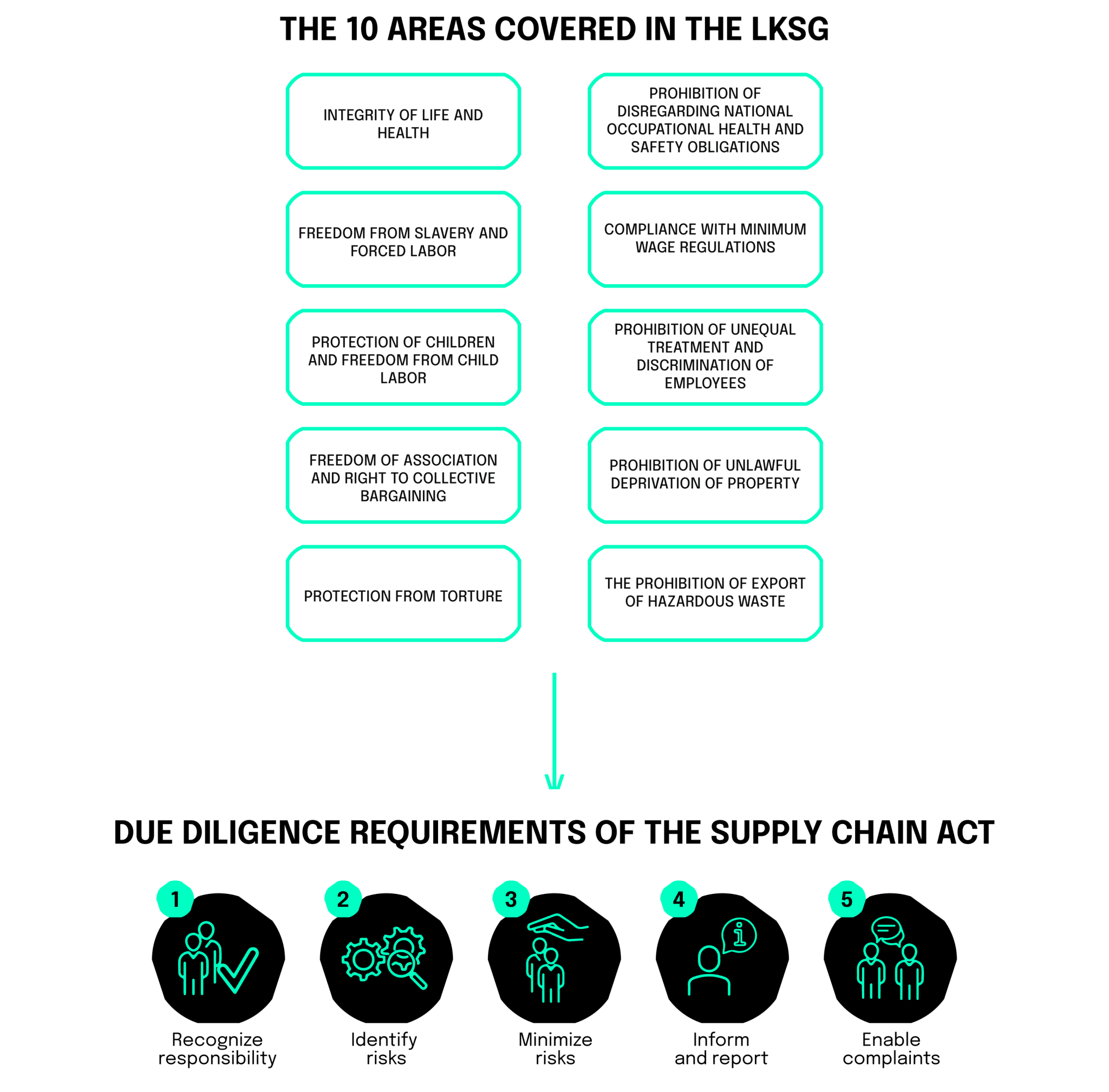

In terms of content, the LkSG covers the 10 following areas, within which 5 specific duties of care must be applied:

More detailed information about the LkSG can be found here.

Enforcement of the LkSG

Compliance with the due diligence requirements must be documented internally in each company and submitted in an annual report to the Federal Office of Economics and Export Control (BAFA) for review. If the BAFA identifies a company’s failures or violations, it must pay fines or is excluded from public tenders and contracts. Penalties can thus amount to up to 8 million euros or up to 2% of the company’s annual turnover.

What we are missing in the LkSG

We see potential for improvement in the LkSG both in its implementation and in the scope covered. On the one hand, the due diligence obligations are limited only to the company’s own business operations and its direct suppliers and business partners. For example, in Clause 9, a risk analysis of indirect suppliers is only due if the diligent company obtains substantiated knowledge of legal violations at these suppliers. In addition, the LkSG does not provide for civil liability in the event of violations of due diligence obligations. Nor can those affected by human rights violations sue companies for damages.

Furthermore, environmental factors are hardly included in the LkSG unless they have a direct negative impact on human health. Considering the ecological problems we face, we believe that too little attention is paid to environmental due diligence.

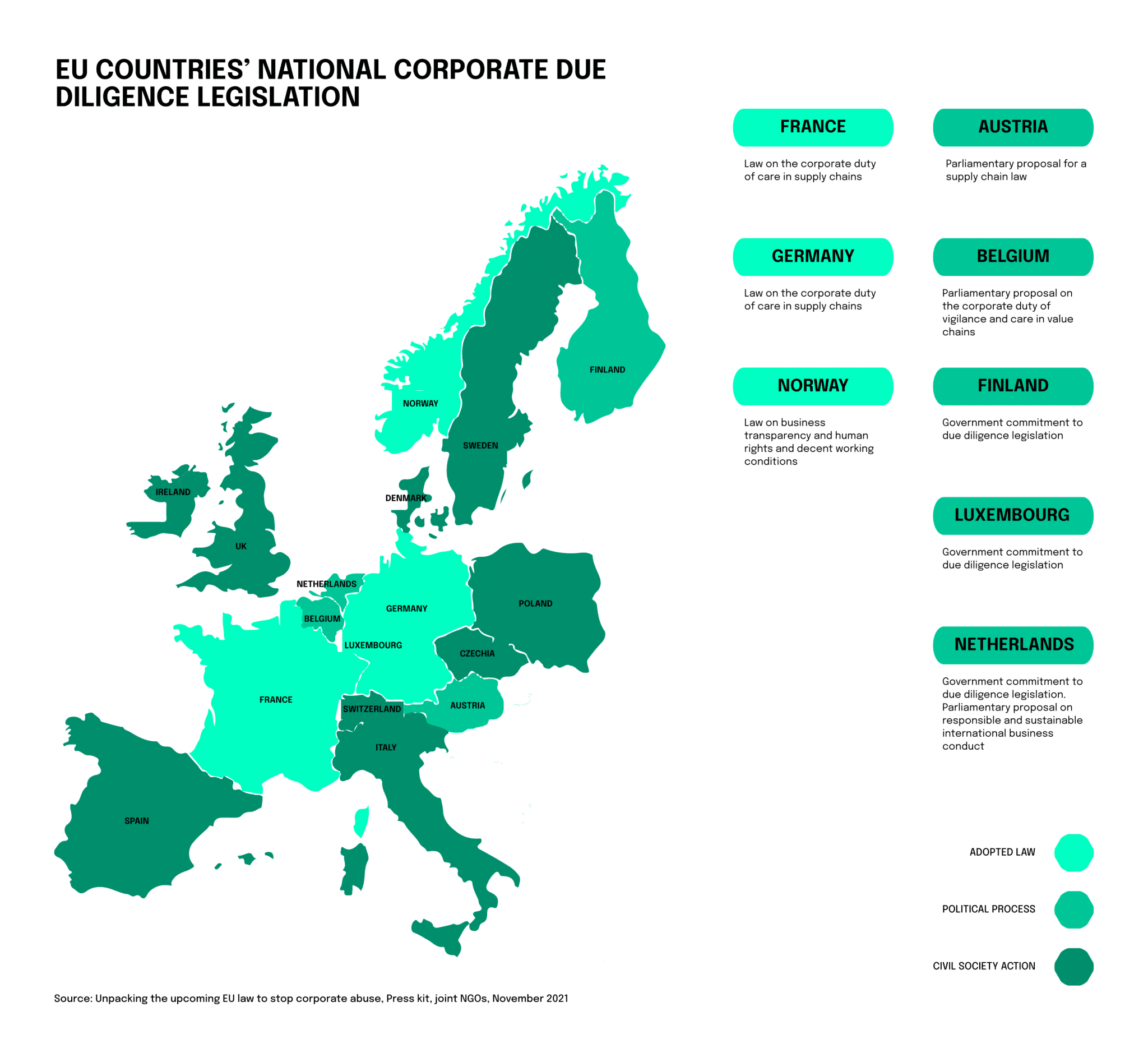

The German LkSG thus has some opportunities for further enhancements. But what about our neighboring countries? Are there more comprehensive laws there? The following chart gives an overview of other national action plans. If you want to learn more about the individual initiatives and laws, see here and here.

Two prominent examples of national action plans are France and the Netherlands.

In 2017, France was the first country to launch a legally binding law, the Loi de Vigilance. While the substantive requirements for human rights and environmental due diligence are largely the same as with the LkSG, the Loi de Vigilance has more in-depth liability rules. Thus, in France, a breach of due diligence can lead to civil liability for the company, and victims of human rights violations can sue for damages against the company that failed to comply with its due diligence obligations. The French law thus has a considerable signal character in terms of legal policy.

The Netherlands also passed a Child Labor Due Diligence Act in 2019, but the clear focus here is the fight against child labor. The main difference to the French and German solution is that Dutch companies must review their entire supply chain, including indirect partners.

However, the environmental factors we mentioned earlier are not sufficiently considered in these laws either and also represent potential for improvement and tightening up here.

A uniform european standard

Now, much has been said about the action plans of individual European states – but little about the role of the European Union (EU). The EU, as the link in our European community, plays an important role in many areas in setting common standards and monitoring their implementation.

In analyzing the various laws and action plans, the EU has noticed that too little is still being done at the national level and that there are weaknesses in each of the existing laws. As a consequence, the European Commission (EC) launched a legislative proposal for the Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (CSDDD) on February 23, 2022. The aim of the CSDDD is to refine and create a uniform framework at European level and to mitigate the weaknesses of existing national laws.

As of today, however, the CSDD has not yet been officially passed yet. The proposal is being debated in the EU Parliament and is expected to be passed in 2023. Subsequently, the member states have 2 years to transpose the directive into national law. Under the current proposal, approximately 17,000 companies in the EU would be directly affected by the law – starting in 2025 at the earliest.

Under CSDD, the following supply chain offenses would be punishable: Forced labor, child labor, inadequate occupational health and safety, worker exploitation, environmental violations such as greenhouse gas emissions, pollution, or the destruction of biodiversity or ecosystems (biodiversity).

Compared to national laws, the focus is thus to be significantly increased on environmental protection in the supply chain in addition to compliance with human rights standards.

In summary, the current CSDD proposal can be seen as a combination of the strengths from the German, French and Dutch laws. If you want to learn more about the CSDDD, as well as how it differs from the LkSG and the Loi de Vigilence, we recommend this and this podcast.

Nevertheless, the CSDD proposal is subject to clear criticism. Industry representatives, for example, see a bureaucracy monster growing up in this new law. The fear is that companies will be extremely paralyzed by the due diligence requirements. The control and permanent monitoring of the supply chain is seen as an increasing burden for affected companies, which have already suffered recently from the Corona pandemic, increased energy costs, or supply bottlenecks. Even before the CSDD came into force, a survey revealed that half of German companies see major challenges in complying with due diligence requirements. Almost as many companies would like external support in complying with the CSDDD for this very reason.

Technology as a problem solver

So on the one hand, companies are already overstretched, while at the same time regulatory and social pressures continue to increase. The question now is what role technology can play in solving the supply chain problem.

As impact venture capital investors who’s daily aim it is to fight social and economic problems with technical solutions, we see a solution to the problem in the ideas of ambitious founders who make the collection, evaluation, and reporting of information easier and more transparent – true to the motto “tech is here to help”. Some examples below:

- AI-based data capture: gives companies the ability to capture existing data in an orderly fashion and convert it into reporting formats. This saves time and money and increases the accuracy of the information captured.

- Drones: are suitable to be used specifically for certain audits that have not yet been automated and are usually costly, difficult, and sometimes dangerous to perform. For example, audits in large warehouses or in the open air. Thus, they can enhance the auditor’s capabilities in observation, inspection, evaluation, and execution.

- Blockchain: traditional supply chains typically use paper-based and siloed information systems that make tracing products and their delivery routes a time-consuming task. This is where blockchain can reduce cost, time, and opacity. Global supply chain companies document updates in a single shared “ledger” that provides complete data transparency and a single source of information. Because each transaction is timestamped, companies can query the status and location of a product at any time and control all parties involved.

- AI-powered social media monitoring: can provide insights into the social media profiles and audiences surrounding a business. This often leverages the power of AI to analyze social data at scale, understand what is being said in it, and then provide insights based on that information. This knowledge can help identify potential scandals with suppliers or producers and investigate them further in detail at an early stage.

- Web scraping: uses bots to extract content and data from a variety of websites. Using this technology can thus enable potential suppliers to be analyzed more quickly and automatically based on numerous data points. However, the analysis of worker voices on whistleblower sites can also be made much simpler and more efficient through the use of web scraping.

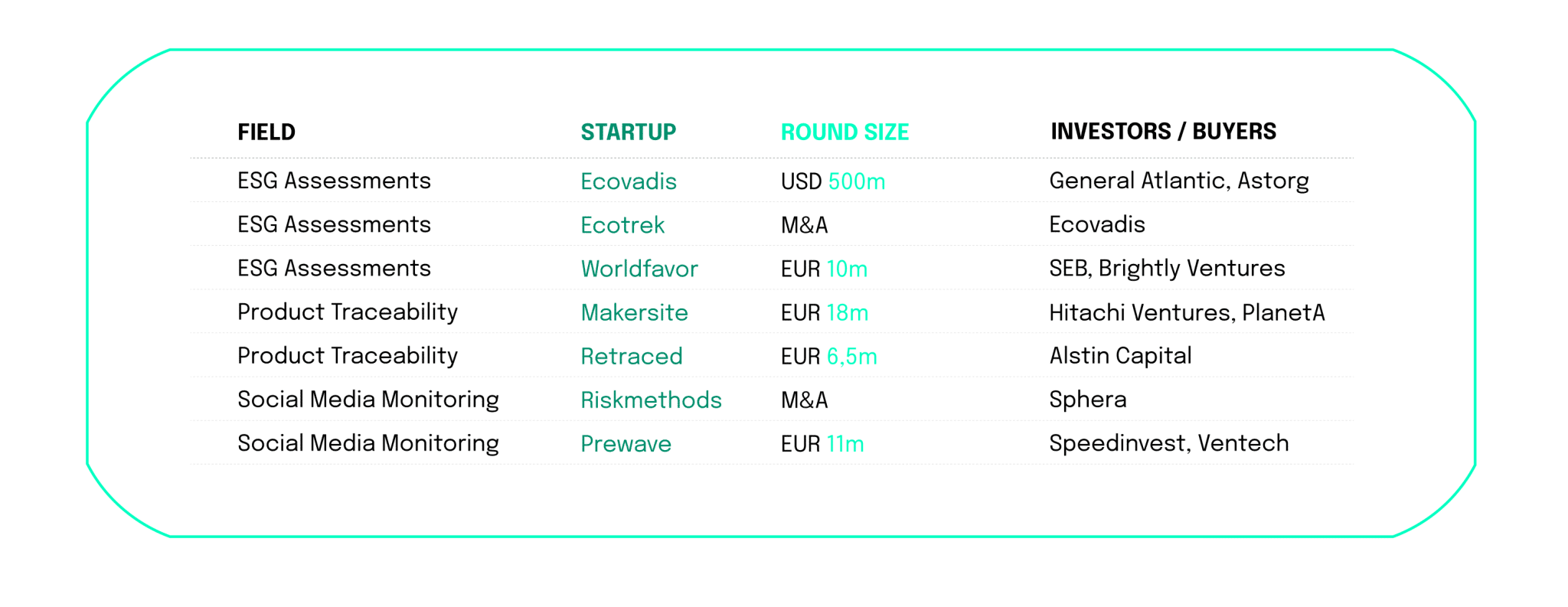

The following overview shows some start-ups, clustered by use case, that use those new technologies in order to enable companies to comply with European standards.

Current investor focus

The relevance of the supply chain issue has already been recognized by many investors. For example, in the first half of 2022 alone, USD 857m in funding flowed into supply chain sustainability startups, more than in the previous 3 years cumulatively. The following table shows an excerpt of recent financing rounds and M&A transactions:

Potential for further innovation and outlook

So what is the takeaway of all this? The first thought that comes to mind is that there has been a lot of innovation and capital allocation around sustainable supply chains. So what’s left to do then?

Simplified, the integration of analysis and reporting with pragmatic, automated decarbonization of supply chains. The job that typically climate consultants do today, will have to be covered by technology in the future, if smaller- and medium sized companies (SMEs) are to decarbonize their business practices efficiently.

That will mean, as a first step, integrating today’s software solutions on direct and indirect supply chains and logistics software, and as a second step, identifying potential improvements and matching them with off-setting providers.

And while startups will have to deliver the technology, the role of the legislature will be to incentivize companies to optimize their economic practices beyond “the bare minimum” – on a social and environmental level. We look forward to following what further developments there will be in this area in the future.

Appelbaum, D., & Nehmer, R. A. (2017). Using Drones in Internal and External Audits: An Exploratory Framework. Journal of Emerging Technologies in Accounting, 14(1), 99–113. https://doi.org/10.2308/jeta-51704

Auswärtiges Amt. (2016). Nationaler Aktionsplan Umsetzung der VN-Leitprinzipien für Wirtschaft und Menschenrechte. In Auswärtiges Amt. Auswärtiges Amt im Namen des Interministeriellen Ausschusses Wirtschaft und Menschenrechte.

https://www.auswaertiges-amt.de/blob/297434/8d6ab29982767d5a31d2e85464461565/nap-wirtschaft-menschenrechte-data.pdf

Bundesministerium für Arbeit und Soziales. (2021, September). CSR – Lieferkettengesetz. www.bmas.de. https://www.csr-in-deutschland.de/DE/Wirtschaft-Menschenrechte/Gesetz-ueber-die-unternehmerischen-Sorgfaltspflichten-in-Lieferketten/gesetz-ueber-die-unternehmerischen-sorgfaltspflichten-in-lieferketten.html

Damoah, I. S., Ayakwah, A., & Tingbani, I. (2021). Artificial intelligence (AI)-enhanced medical drones in the healthcare supply chain (HSC) for sustainability development: A case study. Journal of Cleaner Production, 328, 129598. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.129598

European Commission. (2022, February 23). Nachhaltigkeitspflichten von Unternehmen. https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/de/ip_22_1145

Hembach, H. (2022). Praxisleitfaden Lieferkettensorgfaltspflichtengesetz (LkSG). Fachmedien Recht und Wirtschaft.

Paul, K., & Lydenberg, S. D. (1992). Applications of corporate social monitoring systems; types, dimensions, and goals. Journal of Business Ethics, 11(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf00871986

Rejeb, A., Rejeb, K., Simske, S. J., & Treiblmaier, H. (2021). Drones for supply chain management and logistics: a review and research agenda. International Journal of Logistics Research and Applications, 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/13675567.2021.1981273

Rothermel, M. (Ed.). (2022). LkSG – Lieferkettensorgfaltspflichtengesetz: Kommentar (1. Auflage 2022). Fachmedien Recht und Wirtschaft in Deutscher Fachverlag GmbH.

Shorrocks, A., Lluberas, R., & Davies, J. (2022, January). Global Wealth Report. Credit Suisse. https://www.credit-suisse.com/about-us/en/reports-research/global-wealth-report.html

Short, J. L., Toffel, M. W., & Hugill, A. R. (2020). Improving Working Conditions in Global Supply Chains: The Role of Institutional Environments and Monitoring Program Design. ILR Review, 73(4), 873–912. https://doi.org/10.1177/0019793920916181

neosfer GmbH

Eschersheimer Landstr 6

60322 Frankfurt am Main

Teil der Commerzbank Gruppe

+49 69 71 91 38 7 – 0 info@neosfer.de presse@neosfer.de bewerbung@neosfer.de