30min reading time

Disclaimer:

This insight article is written in cooperation with the IMPACT FESTIVAL .

The IMPACT FESTIVAL is Europe’s largest B2B fair and conference for sustainable innovation and technology. It aims to accelerate the green transformation of our economy by creating a platform for start-ups, corporates, experts, and investors to connect, exchange knowledge and foster implementation of sustainable innovation. On October 5 and 6, 2022, the second edition of the IMPACT FESTIVAL will take place at the Fredenhagen Hall in Offenbach am Main. Learn more about it and get your ticket now: https://impact-festival.earth/

The war in Ukraine, floods in Pakistan and extreme droughts in other parts of the world –

our planet is facing enormous challenges. If humanity is to survive, it must succeed in decoupling the exponential growth of science, technology, and the economy, which has brought us so much prosperity and security for around two centuries, from the equally exponentially increasing exploitation of natural resources. In the areas of raw materials and energy, the aim is to force accelerated development upward into a curve and into a circular economy in line with nature’s processes.

A smart and innovative circular economy connects climate protection, resource efficiency

with an innovative approach to the economy and a prosperous perspective on the future. In

this approach lies gigantic potential that we need to extract and use for good. This will

require joint efforts in science and industry, society and politics.

This article will give you a detailed overview of the concept of circular economy in the first section. The second part of the article takes a closer look at the creation and establishment of circular business models and what defines these approaches to creating economic value. We will also highlight some key adoption challenges for businesses in general, whilst also highlighting how you can take circular action already today.

This article is published in cooperation with the Impact Festival, and is the first of two, with the second one taking a more financial focus on CE and how we can create a financial environment that fosters growth of this innovative approach.

Introduction

Let’s start by creating the foundation for a detailed analysis of the circular economy! We will define circular economy, give you a short overview of recent developments and trends in circular economy and show some regulatory developments in the European Union (EU). The term circular economy has over the past few years become more of a buzzword that typically involves the transformation of large parts of already existing industries and value chains from linear to circular flows. The future of circular business models will be based on the re-use of products and materials, and it does not leave behind waste or emissions that incur cost, cause the use of resources, or impede the lives of future generations. It also involves the large-scale use of biologically based materials to replace plastics and other non-renewable materials.

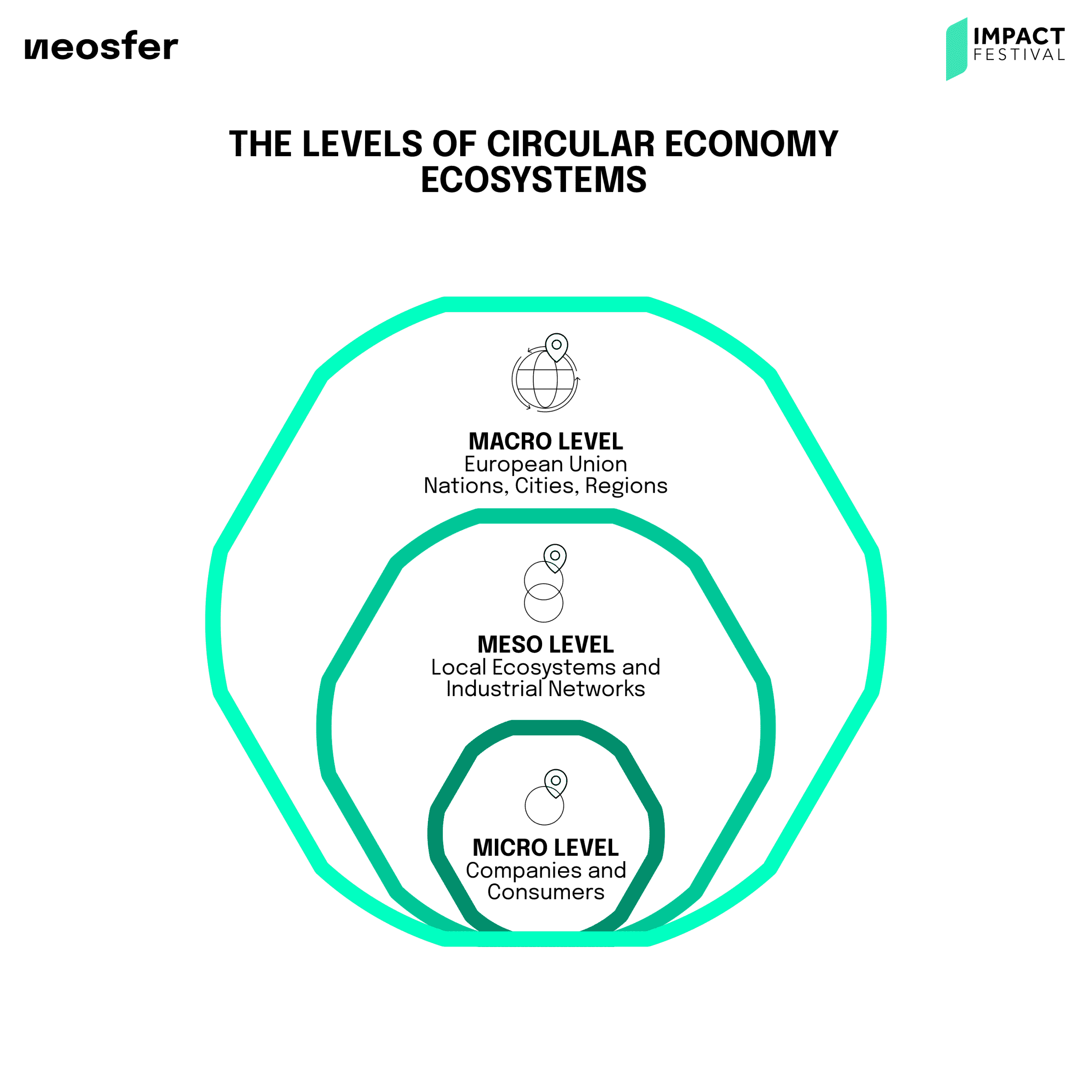

For many, the idea of a circular economy is more of a vision, much talked about, but still a vision. We want to take this vision and show you as the reader a clear roadmap of how circular economy can be defined, and how circular business models can be created. So, we first need to build a basic understanding of circular economy. Circular economy strives to contribute to achieving sustainability goals such as the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). As we already discussed, circular economy is based on the vision of closed resources and product cycles powered by renewable energy. The concept describes an ecosystem where values are created and maintained sustainably. Transferring this vision into a realistic economy requires an ecosystem perspective on the micro, meso and macro level, including companies, local networks and the support of governments and global partnerships. To boil everything down into a one sentence definition, we adopt the definition of Stahel and Clift from 2015: Circular Economy is an economy that focuses on value preservation, encompassing all activities that reduce the material input of production and extend the service-life of goods, components, and materials.

Not only the private sector is active in generating new solutions and taking first steps towards a circular approach to business. The EU is also active in generating an environment in which circular businesses can thrive. The European Commission (EC) adopted the new circular economy action plan (CEAP) in March 2020. The CEAP is not a single regulatory framework. It must be seen as one of the key regulatory pieces of the European Green Deal, the sustainable roadmap towards a greener European economy. So, the CEAP and the implementation of the supposed actions is a prerequisite to achieve the EU’s 2050 climate neutrality target and to halt biodiversity loss. The new action plan announces initiatives along the entire life cycle of products. It targets how products are designed, promotes circular economy processes, encourages sustainable consumption, and aims to ensure that waste is prevented, and the resources used are kept in the EU economy for as long as possible.

But what exactly does this approach look like in theory? The next section will answer this question before we dive deeper into the circular business models and how companies can already take circular actions today.

Circular economy in theory

It is evident that our current production and consumption systems are not sustainable at all. Between 1970 and 2015 our global annual natural resource extraction grew from 27 billion tonnes to 92 billion tonnes, due to factors such as population growth, out-dated modes of production that employ inefficient technologies, and higher consumption as a result of changing consumer habits and purchasing power. Our natural resources extraction contributes to more than 90 percent of global biodiversity loss and water stress impacts, and approximately 50 percent of global greenhouse gas emissions. However, the interest in circular approaches to doing business is not a new concept at all. The history of circular economy, the building blocks of the approach and the fundamental differences between circular and linear economy will be discussed next.

The levels of circular economy

We have already seen and mentioned that the EC and the EU try to create an ecosystem in which a circular economy can thrive. This is the right approach to thinking about circular economy, as this innovative business model can only work if a micro, meso and macro level of the circular economy ecosystem are created, aligned and working together.

Starting with the Macro Level of the ecosystem: here we clearly need the EU and the EC as the large regulatory bodies, aligning all parts of the social and economic society with common high-level goals. This can be done by the efficient communication of new business goals, but also with environmental and sustainability goals. Additionally, single cities and regions also play a critical role in enabling a circular economy. By creating hubs for circular solutions, making it more attractive for entrepreneurs to engage in circular action and making the collaboration between larger corporations and disruptive start-ups easier.

On the Meso Level, it is all about creating local networks and connection of thought leaders of different industries to foster green innovation and transformation. This can be done by expert fairs e.g., the Impact Festival;), events, or traditional trade associations. It is about the transfer of knowledge, the alignment of business actions and the discovery of new challenges and opportunities. Additionally, we cannot neglect the influence of the academical world in creating a new wave of circular frameworks and impact measurements. Besides research, academia is an essential part of developing circularity-focused people willing to engage in sustainable transformation.

On the Micro Level of the circular economy ecosystem, the individual organizations and consumers are located. Ultimately, we need organizations that are willing to implement larger regulatory and academic frameworks into reality. The awareness needs to be created that circular economy is a process and can already be started today with the first steps towards organizational change. Nonetheless, we cannot neglect the impact that changed consumer behavior can have. If we all are more aware of our power, circular products and services are more visible, and we are willing to engage with these solutions, the consumer is a central piece of the circular economy ecosystem.

This circular ecosystem approach can be linked to the general movement called “Regenerative Economy”. These economies have the goal of regenerating capital assets. What sets regenerative economics apart from standard economic theory is that it considers and gives hard economic value to the principal or original capital assets — the earth and the sun. Therefore, most of Regenerative Economics focus on the earth and the goods and services it supplies. Out of this reason, the regenerative economy can still work in a capitalistic or social market economy by just taking the earth as a capital asset to protect and nurture. Recognizing the earth as the original capital asset places the true value on the environment. And by not having this original value properly recognized has created the unsustainable economic condition referred to as uneconomic growth, a term first coined by Herman Daly.

Circular Economy vs. Linear Economy

So, how exactly is the circular economy different from a linear economy?

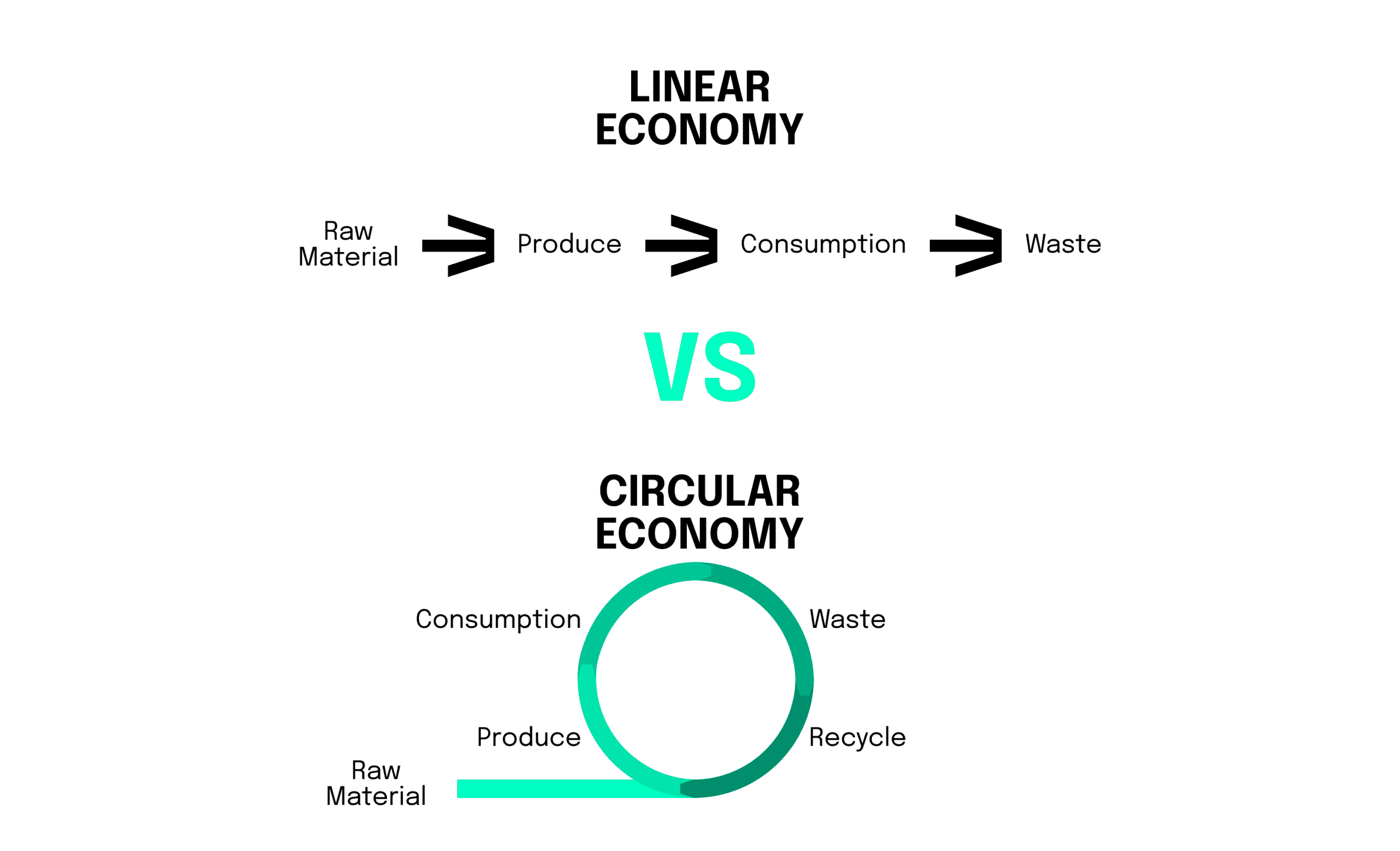

A linear economy operates on a ‘take-make-dispose’ model, making unbounded use of resources to produce products that will be discarded after use. A circular economy, in contrast, centers around the reuse of products and raw materials, and the prevention of waste and harmful emissions to soils, water and air, wherever possible (“closing the loop”).

The conversion of a linear economy into one that is circular involves systems changes, or transition. Other designs or processes, products that can be repaired or regenerated, recycling of materials and another way of thinking about products, are all aspects of such a change.

As it is clearly observable, the circular economy is way more than just the redesign of products or the recycling actions of a product at the end of its lifecycle. To move away from a linear approach we need disruptive innovations in supply chain management, the extensive creation of renewable energy sources and a change of mind when looking at the earth as our original capital asset that we need to protect and nurture.

Definition of circular business models

By taking a closer look at circular economy as a biological and technical cycle, we can start to understand how circular business can be created. With consideration of the aspirations of circular economy, we will give you insights into the operational creation of circular businesses thanks to the Value Hill approach and the underlying five headline business models.

Circular Economy as a biological and technical cycle

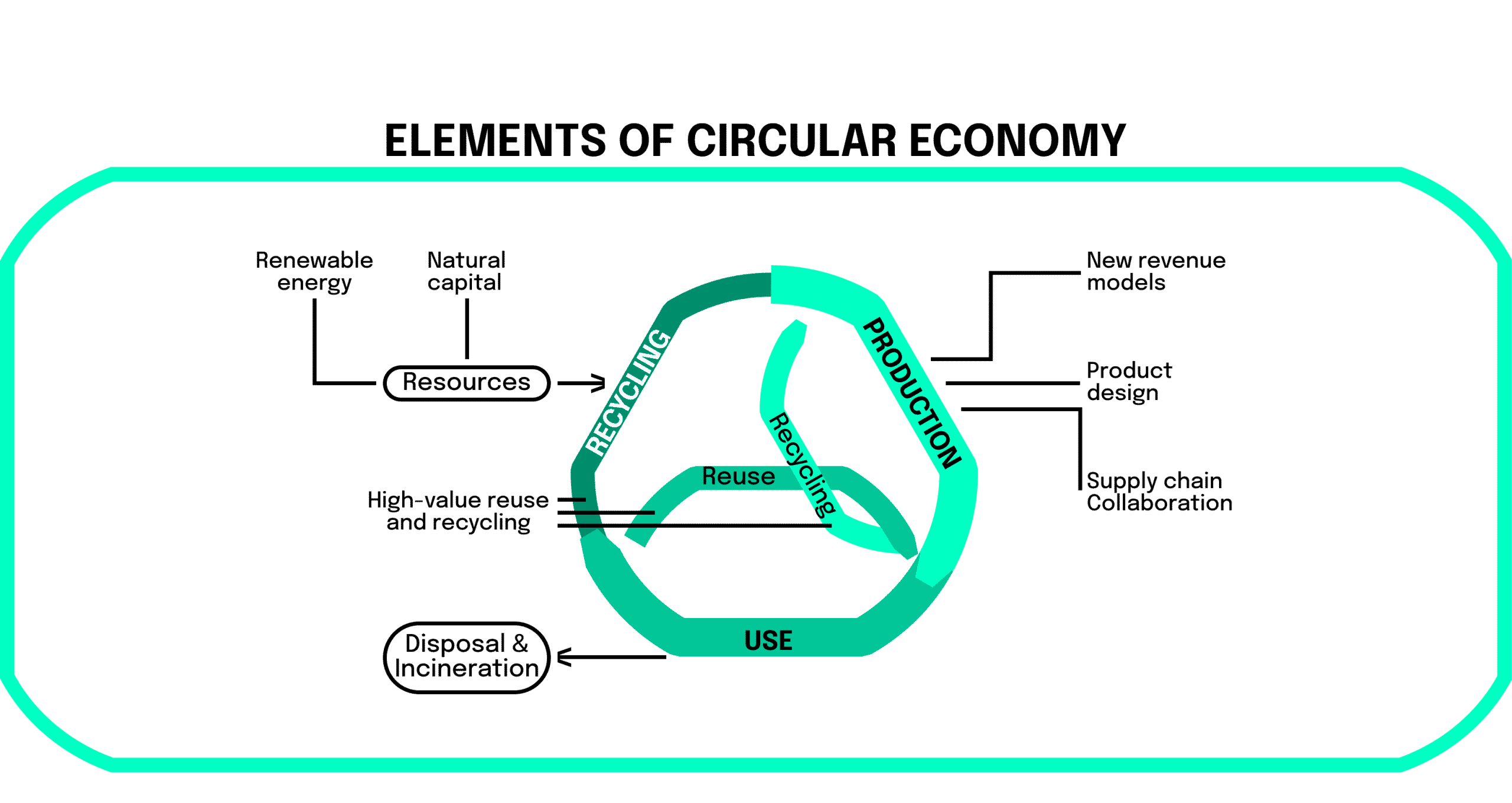

A circular business model articulates the logic of how an organization creates, offers, and delivers value to its broader range of stakeholders while minimizing ecological and social costs.

Circular businesses no longer focus mainly on profit maximization or pursue cost-cutting through greater efficiency in supply chains, factories, and operations as the primary corporate objective. Rather, they concentrate on redesigning and restructuring business strategies from the bottom up to ensure future viability of business activities and market competitiveness.

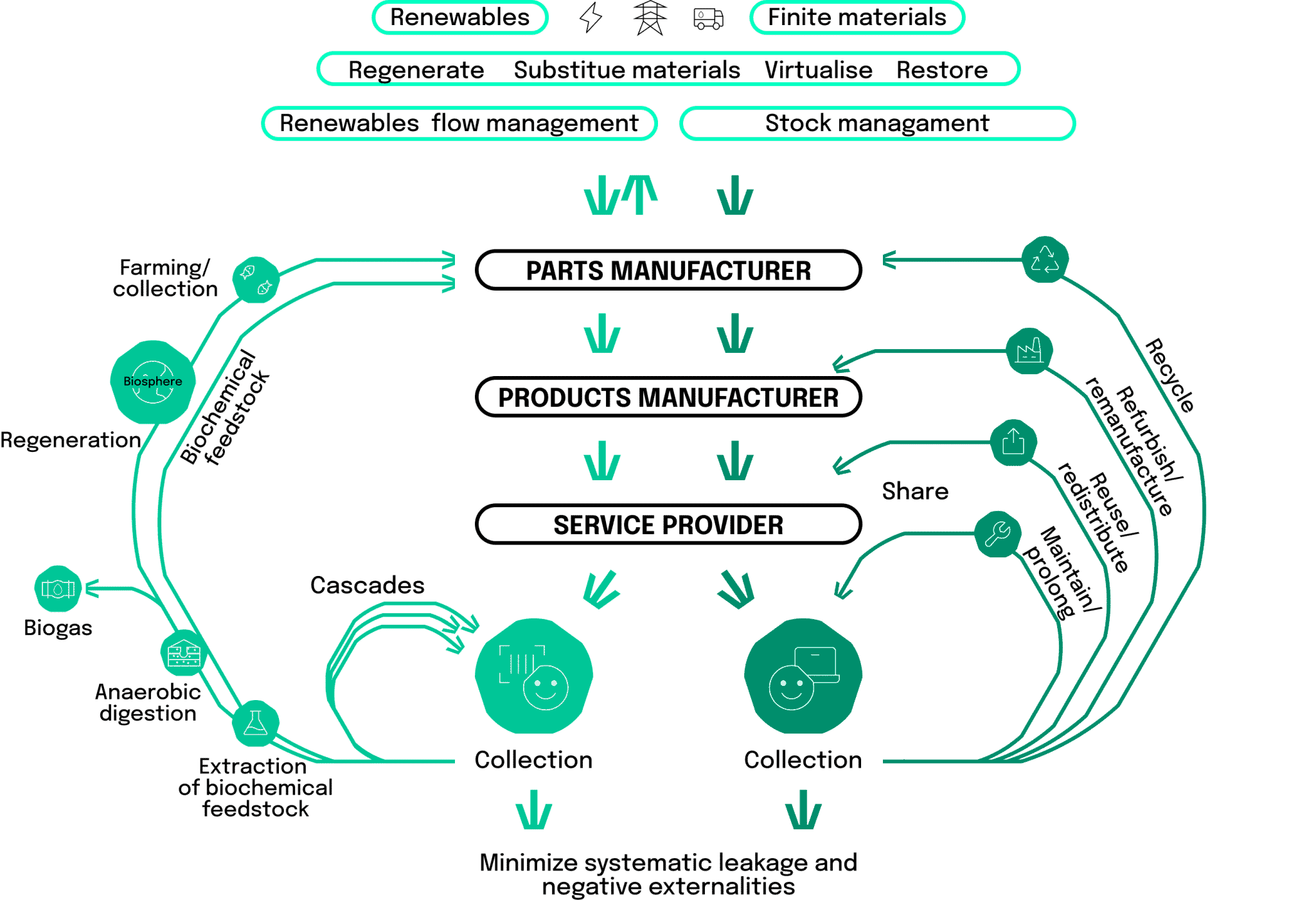

The circular economy system diagram, known as the butterfly diagram shown below, illustrates the continuous flow of materials in a circular economy. There are two main cycles – the technical cycle and the biological cycle. In the technical cycle, products and materials are kept in circulation through processes such as reuse, repair, remanufacture, and recycling. In the biological cycle, the nutrients from biodegradable materials are returned to the Earth to regenerate nature. his circular framework was established by the Ellen MacArthur Foundation.

The biological cycle

The left side of the butterfly framework displays the biological cycle. This cycle depicts the processes that return nutrients to the soil and help regenerate nature. At the heart of the biological cycle is the concept of regeneration. Instead of continuously degrading nature, as we do in the linear economy. No longer should the focus be on what we can do to reduce harm to the environment but rather how we can actively regenerate our natural ecosystem.

With farming as the next step in the diagram, we can manage farms and other sources of biological resources in ways in that create positive outcomes for nature. These outcomes include, but are not limited to, healthy and stable soils, improved local biodiversity, improved air and water quality, and storing carbon in the soil. The benefits for the consumer are also obvious, as products from regenerative farms generally are more nutritious and therefore healthier options compared to other foods.

Besides more well-known concepts of composting, there is also the building block called “Cascades”. These loops in the biological cycles make use of products and materials already in the market. This could mean using food by-products to make other materials, such as textiles made from orange peel, or designing new food products using ingredients usually considered waste, like ketchup made from banana peel or beer made from bread waste. If products or materials cannot be used at all, they move to the outer loops of the biological cycle where they are returned to the soil and our natural capital asset, the earth.

As the final step of the biological cycle, you can observe the extraction of biochemical feedstock. Taking post-harvest and post-consumer biological materials as feedstock, this step needs biorefineries to produce low-volume but high-value chemical products. These processes could consecutively produce, for example, high-value biochemicals and nutraceutical followed by bulk biochemicals.

The technical cycle

On the right side of the butterfly diagram is the technical cycle. This cycle includes all products and resources that are used rather than consumed. We will observe a couple of the key steps that allow materials to remain in use rather than becoming waster after a short period of time.

It is important to differentiate between the inner and outer loops of the cycle. The inner loops are where most value can be captured because there, the value embedded in the products and resources is maintained. Inner loops like sharing, maintaining, and reusing should be prioritized above the outer loops that see the product broken down and remade. These loops also represent a cost saving to customers and businesses as they make use of products and materials already in circulation, rather than investing in making them new.

The outermost loop, recycling, is therefore the stage of last resort in a circular economy because it means losing the embedded value of a product by reducing it to its basic materials.

Ambitions of circular economy

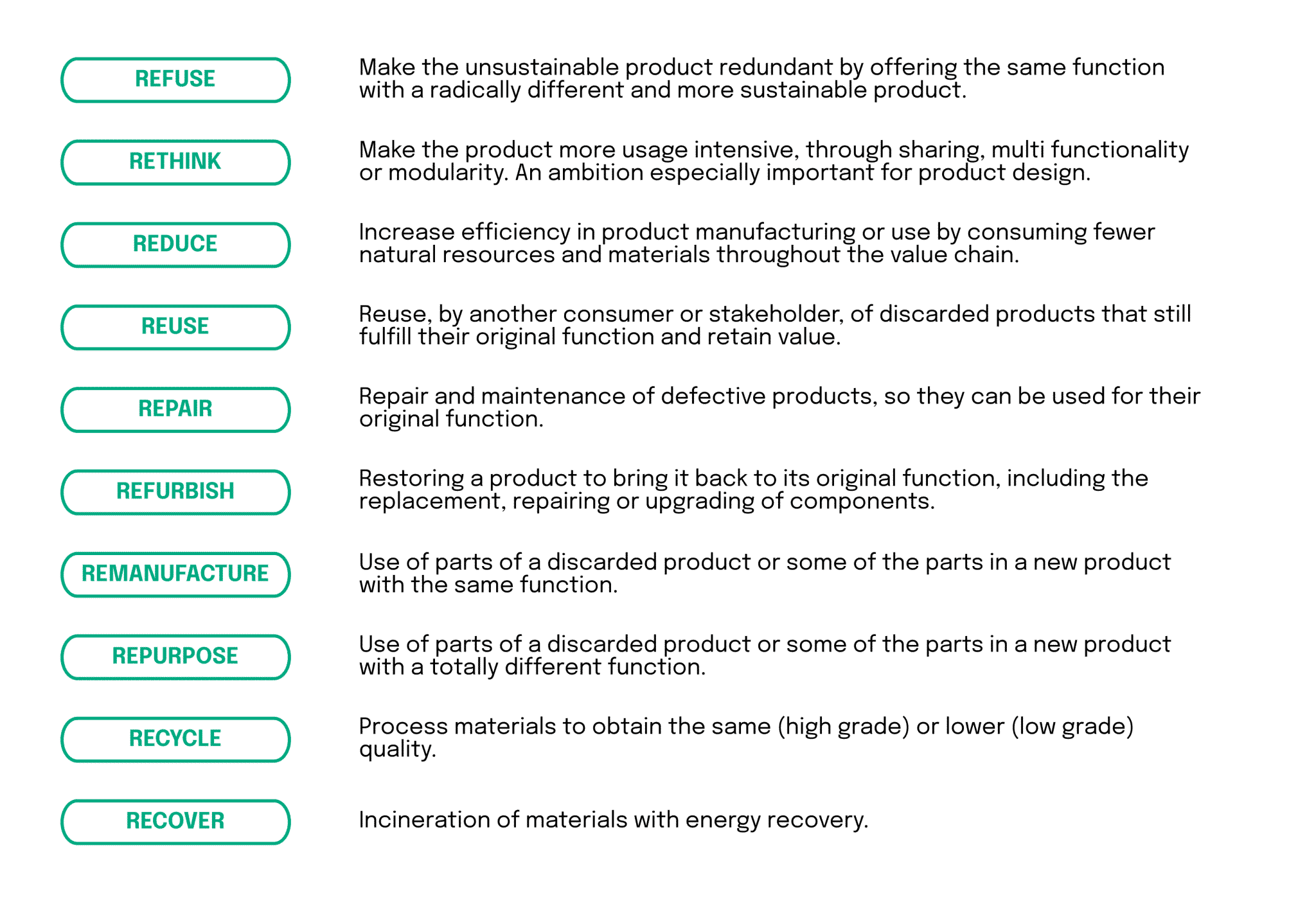

Within the butterfly diagram there are recurring ambitions of the cycles and the different loops observable. The different ambitions that circular business should implement in their strategy, vision, or mission can be summarized with the ten R’s.

However, these ten ambitions should not only act as a guide for businesses, they can also give direction to the consumer. They can remind us that we need to be more aware of the potential impact we can have in transforming society and how we can change our individual behavior to create a more sustainable future. Combining the butterfly diagram with the ambitions of circular economy, we can come to the most used way to describe and analyze circular business models: the Value Hill Approach.

Circular businessmodels

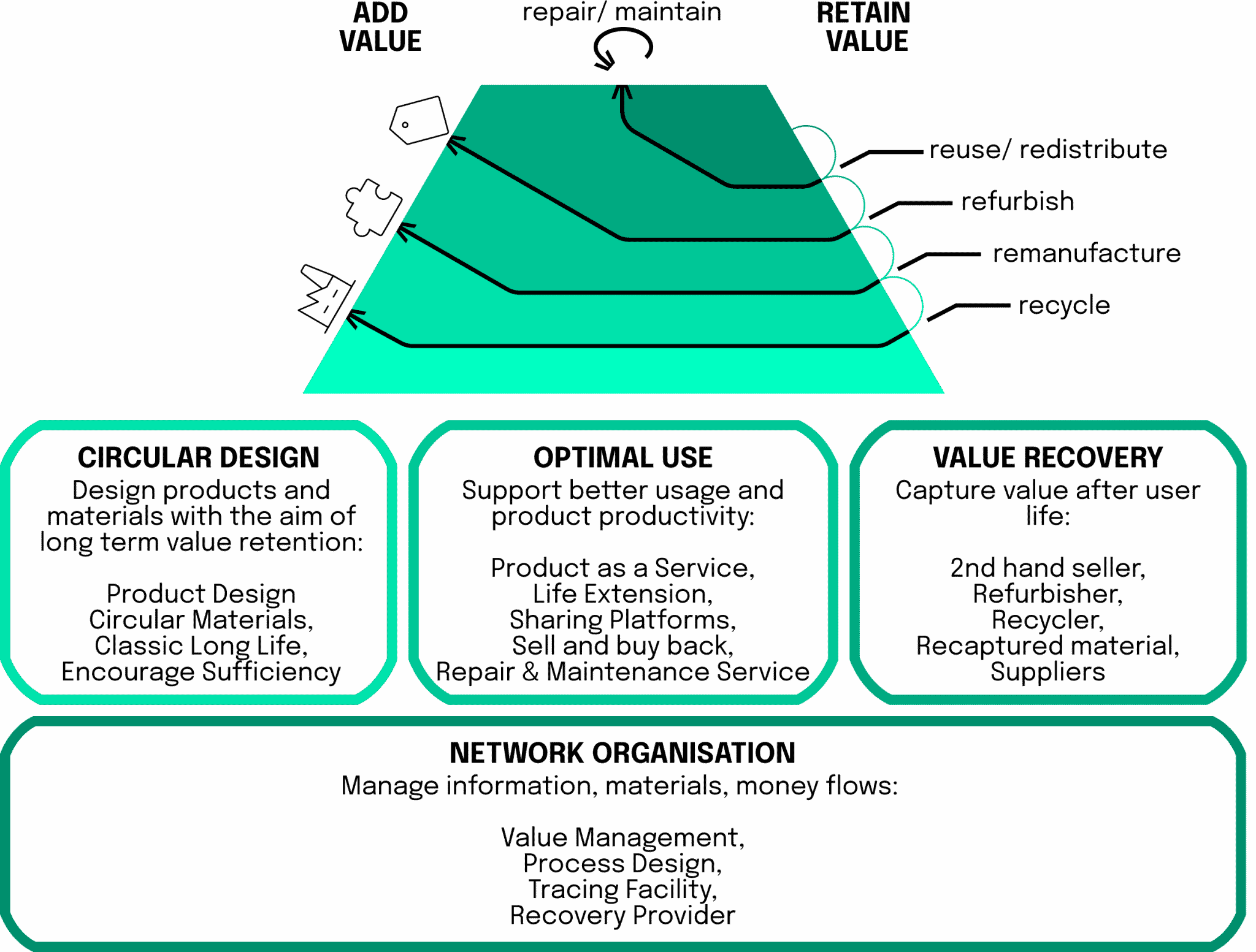

Understanding the Value Hill Approach will give us the opportunity to identify five core business models of circular business and understand how they can touch all part of the value chain. Whilst linear business models just focus on the left side of the Value Hill, we will shortly discover that circular businesses have a more holistic approach and extend the linear approach with value-retaining actions.

The Value Hill approach

In the context of the Value Hill, value is added while the product moves “uphill” and circular strategies keep the product at its highest value (top of the hill) for as long as possible. Products are designed to be long-lasting and are suitable for maintenance and repair, thus slowing resource loops and prolonging the use phase of the product. When a product is ready to start its downhill journey, it is done as slowly as possible so that its useful resources can still be of service to others.

The path that products take while travelling up and down the Value Hill is divided in three phases. The pre-use phase (mining, production, distribution) is displayed on the left as value is added in every step and the product moves uphill. The second phase is the in-use phase and is depicted at the top of the hill. Here the value of a product is at its highest. And the third phase is the post-use phase, where the product loses value as it moves downhill. In the last phase, it is especially important that products are arriving at a previous phase. Therefore, the third phase is critical for the introduction of new value and previously existing value is retained.

To establish circular ecosystems, there must be substantial change and evolution in the way we all do business. To maintain control of resources and preserve a product’s value, the different activities can be categorized among four categories on the Value Hill: Circular Design, Optimal Use, Value Recovery, and Network Organization. For this all to work, there needs to be a lot of collaboration, exchange, and communication between all the circular stakeholders.

The first category, Circular Design, fits to business activities that occur during the pre-use or the design, or production and distribution of a product. These activities are positioned on the upward slope of the Value Hill and are focussed on prolonging the use phase or try to make sure that intentionally, the products are easier to enhance in the phase where value should be retained, for example through modularity of the product.

The second category, Optimal Use, relates to the in-use phase of a product. Business models in this category seek to optimize the use of the product by providing services or add-ons to extend the lifetime of a product or provide ways to improve productivity of a product. These business models are positioned on top of the Value Hill.

The third category involves the post-use phase of a product. These business models generate revenue by capturing the value from used products (formerly known as waste or by-products). Value Recovery involves using recaptured materials, providing refurbished products, Downhill: Value Recovery selling second hand products, and facilitating remanufacturing and recycling.

The last category, Network Organization, involves business activities that involve the management and coordination of circular value networks. This entails coordination and management of resource flows, optimizing incentives and other supporting activities in a circular network. In this category, we do not only want to place emphasis on businesses but also want to highlight the importance of trade associations, network events and fairs that support businesses in finding new investors, partners and simplify the flow of information and innovative ideas.

The three phases, and four categories we just described, are interrelated with the butterfly diagram highlighted in the sections before. Additionally, you can find a lot of the inner and outer loops of the butterfly diagram in the Value Hill Approach. Based on this knowledge, there are five core business models identifiable that we briefly highlight in the next section, with additional real-life examples of start-ups following a particular model.

Five headline business models

The move to a circular business model is an example of a fundamental change, which requires a new way of thinking and doing business. The following identified circular business model typology provides opportunities for implementing the idea of circularity at a practical level. It should be noted that the briefly described types do not necessarily present full business model innovations, but rather, key elements of strategies that contribute to a circular business.

Circular supply models, by replacing traditional material inputs derived from virgin resources with bio-based, renewable, or recovered materials, reduce demand for virgin resource extraction eventually. A great example of this circular business model at work is the company RE-ZIP. Online customers choose circular packaging at checkout. After delivery, the packaging is collapsed to a convenient return format, and the nearest drop point is easily located using the RE-ZIP app. Customers are rewarded with vouchers at the end of the process.

Resource recovery models recycle waste into secondary raw materials, thereby diverting waste from final disposal while also displacing the extraction and processing of virgin natural resources. An innovative company following this model is traceless. They produce traceless materials as a granulate which can be further processed. The materials used are not only a holistically sustainable alternative to conventional plastics and bioplastics, and designed to leave no trace. Additionally, the materials are bio-based and made of natural ingredients, which are by-products of agricultural food production. Other examples for business following this approach are ecoLocked, and ReCollector.

Product life extension models extend the use period of existing products, slow the flow of constituent materials through the economy, and reduce the rate of resource extraction and waste generation. Refurbed can be seen as one of the key companies following this approach. You can sell your used hardware to them, they exchange singular parts and sell them again on the marketplace. Refurbishing reduces CO2 emissions by around 70% compared with new production. For a cell phone, that’s around 43 kg of CO2, for a laptop around 210 kg. Another company related to this approach is Fairphone. They produce modular smartphones that make the refurbishment process more accessible to the everyday consumer, without the need for an engineering degree.

Sharing models facilitate the sharing of underutilized products, and can therefore reduce demand for new products and their embedded raw materials. Grover, which offers pay-as-go subscription plans to its customers, has been described in some outlets as something like a Netflix for gadgets. Here, you can rent hardware devices as long as you need them, and then just sending them back. This promises to reduce hardware in circulation and therefore saving environmental pollution. A similar idea can be observed when looking at the company circulee, that focuses on the B2B business side of things.

Product service system models, where services rather than products are marketed, improve incentives for green product design and more efficient product use, thereby promoting a more sparing use of natural resources. An impactful example of this business model at work is the company Ressourcify, which offers recycling and waste management services as software solutions. A use case with their software at work at Hornbach can be viewed here as well.

Adoption challenges for creating circular economies

There are a multitude of different challenges, companies, governments and other stakeholders in the circular economy ecosystem need to solve. We structure the challenges into firm-internal ones and external challenges. This list includes the most pressing issues, while not representing the whole list of challenges.

As far as firm-internal challenges go, we want to focus on the internal knowledge of circular economy and organizational structures that hinder the adoption of circular economy business models and ideas.

Information access and awareness refer to not knowing the necessary information to make informed decisions and is one of the core things needed to build up knowledge about circular economy. For instance, not having access to real data or not knowing which suppliers have low environmental impacts. Innovations like IoT, Big Data, and Blockchain could facilitate some of these concerns. Another barrier within this firm-internal challenge includes the lack of awareness toward circular economy or the environment. To tackle this, research presents enablers, such as clear communication on the circular economy concepts and its success stories within the company.

However, knowledge among the general workforce of a company will not be enough to enable the creation of circular business models. The overall organizational structure of a company can have a big influence on the adoption of circular approaches.

According to Liu and Bai, a firm’s structure influences its behavior in developing circular economy. In this sense, barriers associated with this challenge include inefficient bureaucracies and procedures that hamper innovation and inhibit flexibility. A great way of removing these barriers is to create internal think tanks, where ideas can be created and discussed freely without any of the regular corporate frameworks. Collaborations with other firms and stakeholders through more “traditional” think tanks are a great strategy for structured, yet innovative collaboration.

Besides internal challenges, companies must also tackle externalities that can make the adoption of circular approaches difficult. We want to highlight the adoption problems arising through lack of infrastructure, user behavior and financing.

Infrastructure irregularities refer to barriers linked to faulty infrastructure or its complete unavailability within a region; this can include but is not limited to the waste management or water network infrastructure. Associated barriers can include the lack of effective recovery, transportation, and sorting of waste and the high costs of these activities. This makes it especially tricky to adopt circular approaches for multinational companies operating in many geographical regions or small businesses that operate in a particular region with lacking infrastructure.

However, we as the consumers of most products have an influence on the adoption speed as well. User behavior in that sense refers to the user’s preference or willingness to pay a surplus for a “green” or circular product. In this sense, researchers identified that consumers prefer to buy disposable products as they are usually cheaper or more convenient. In contrast, consumers are likely to switch to circular products if linear products have higher prices. Either through regulatory pressure of pricing negative externalities or the changes in consumer demand, prices of circular products relative to disposable products need to be lower. Social practice theory plays a critical role here, as our use & throw out approach to consumption, observable for example with Coffee to Go, is deeply embedded in the minds of consumers. These automatisms need to be systematically observed, reviewed and changes.

One major external challenge is the access to funding, especially for any new business and start-ups that wants to scale rapidly. As this is one of the major challenges for the adoption of circular business models, we dedicate the second article of this series to exactly this topic.

Circular economy and the SDGs

Lately, the circular economy has gained importance as a tool that presents solutions to some of the most pressing cross-cutting challenges in the sustainable development of our future.

By addressing root causes, the concept of a circular economy, an economy in which waste and pollution do not exist intentional, products and materials are kept in use, and natural systems are regenerated provides much promise to accelerate implementation of the 2030 Agenda. If we can overcome the challenges mentioned above, the creation of circular ecosystem can contribute towards the achievement of key SDGs.

The European Union particularly put emphasis on circular economy and the achievement of the SDG 2 Zero Hunger, SDG 6 Clean Water and Sanitation, SDG 7 Affordable and Clean Energy, SDG 8 Decent Work and Economic Growth, SDG 12 Responsible Consumption and Production, and SDG 15 Life on Land. The UN believes that the circular economy holds particular promise for achieving SDGs 6 on energy, 8 on economic growth, 11 on sustainable cities, 12 on sustainable consumption and production, 13 on climate change, 14 on oceans, and 15 on life on land.

Even if there is disagreement for which SDGs in particular the circular economy can have the biggest impact, both the EU and the UN agree that the transition from a linear to a circular economy requires a joint effort by stakeholders from all sectors. So, a particular focus must be put on SDG 17 Partnerships for the Goals. Companies can contribute to the transition by developing competencies in circular design to implement product reuse, and recycling, and serving as trend-setters of innovative circular economy business models. Policymakers can support the transition by promoting the reuse of materials and higher resource productivity by rethinking incentives and providing the right set of policies. As financial institutions are also part of SDG 17 and access to finance still is a critical adoption challenge, the second article will take a closer look at barriers to invest in circular business models, and innovative financial instruments trying to solve these challenges.

While the specific term circular economy is of relatively recent origin, the idea of including circular approaches to economic activities comes from a long-held debates concerning the sustainability and the (in)compatibility between the economy and the environment. There have already been quite some attempts to capture the true origin of circular thinking and economic approaches. We are just going to list some key books, manuscripts, and resources that are referred to as the earliest written sources of these ideas.

Some origins of Western thinking in terms of circularity have been traced back to the 18th century (François Quesnay 1758; William Forster Lloyd 1833; Thomas Malthus 1798; Peter Lund Simmonds 1862)).

The first real examples of circular policies in action can be seen in the 20th century. In Asia, for example, as communist China emerged in 1949, policies targeting the ‘comprehensive utilization of resources’ were adopted from the Soviet Union and more general pollution and waste policies were implemented in 1995. The term ‘circular economy’ was first proposed as a policy concept in 1998 and has since been broadened from its narrow focus on recycling to resource efficiency based on closed material loops in production, distribution, and consumption.

The first country in the EU to establish a waste hierarchy as a policy principle was the Netherlands with the implementation of the policy happening in 1979. German waste legislation is notable for its introduction of the Packaging Ordinance in 1991, which was a source of inspiration for the EU’s 1992 Packaging and Packaging Waste Directive.

The EU’s first move towards a circular economy can be traced back to the EC’s 2005 communications on Thematic Strategy on the Sustainable Use of Natural Resources (COM(2005) 670) and Taking Sustainable Use of Resources Forward: A Thematic Strategy on the Prevention and Recycling of Waste (COM(2005) 666). However, the term Circular Economy was not really mentioned until the early 2010s. In 2014, the Barroso-led Commission released its circular economy package entitled “Towards a Circular Economy: A Zero Waste Programme for Europe” (COM(2014) 398). This was the first effort to re-implement environmental thinking into the economy after the financial crisis. After a personnel switch at the top of the EC, the Juncker-led Commission replaced the old package by a more ambitious one called “Closing the Loop – An EU Action Plan for the Circular Economy” (COM(2015) 614). This all lead to the Circular Economy Action Plan in place today. Nonetheless, especially for the EC, we cannot overlook the importance of the Ellen MacArthur Foundation: the self-described “global thought leader, establishing circular economy on the agenda of decision makers across business, government, and academia”. This organization acts similar to an advisory or expert group, supporting the EC in the creation of new regulatory frameworks. We will also analyze and present some of the EMF’s frameworks and ideas throughout this article.

Bucci Ancapi, F., Van den Berghe, K. & van Bueren, E. (2022, November). The circular built environment toolbox: A systematic literature review of policy instruments. Journal of Cleaner Production, 373, 133918. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2022.133918

Cantú, A., Aguiñaga, E. & Scheel, C. (2021, 1. Februar). Learning from Failure and Success: The Challenges for Circular Economy Implementation in SMEs in an Emerging Economy. Sustainability, 13(3), 1529. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13031529

Casiano Flores, C., Bressers, H., Gutierrez, C. & de Boer, C. (2018, 10. April). Towards circular economy – a wastewater treatment perspective, the Presa Guadalupe case. Management Research Review, 41(5), 554–571. https://doi.org/10.1108/mrr-02-2018-0056

Fonseca, L., Domingues, J., Pereira, M., Martins, F. & Zimon, D. (2018, 19. Juli). Assessment of Circular Economy within Portuguese Organizations. Sustainability, 10(7), 2521. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10072521

Ranta, V., Aarikka-Stenroos, L., Ritala, P. & Mäkinen, S. J. (2018, August). Exploring institutional drivers and barriers of the circular economy: A cross-regional comparison of China, the US, and Europe. Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 135, 70–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2017.08.017

Trzmielak, D. M., Gibson, D. V., Uniwersytet Łódzki. Centrum Transferu Technologii & Uniwersytet Łódzki. Wydawnictwo. (2014). International Cases on Innovation Knowledge and Technology Transfer. Amsterdam University Press.

neosfer GmbH

Eschersheimer Landstr 6

60322 Frankfurt am Main

Teil der Commerzbank Gruppe

+49 69 71 91 38 7 – 0 info@neosfer.de presse@neosfer.de bewerbung@neosfer.de