20min reading time

The role of governments in enabling impact investing

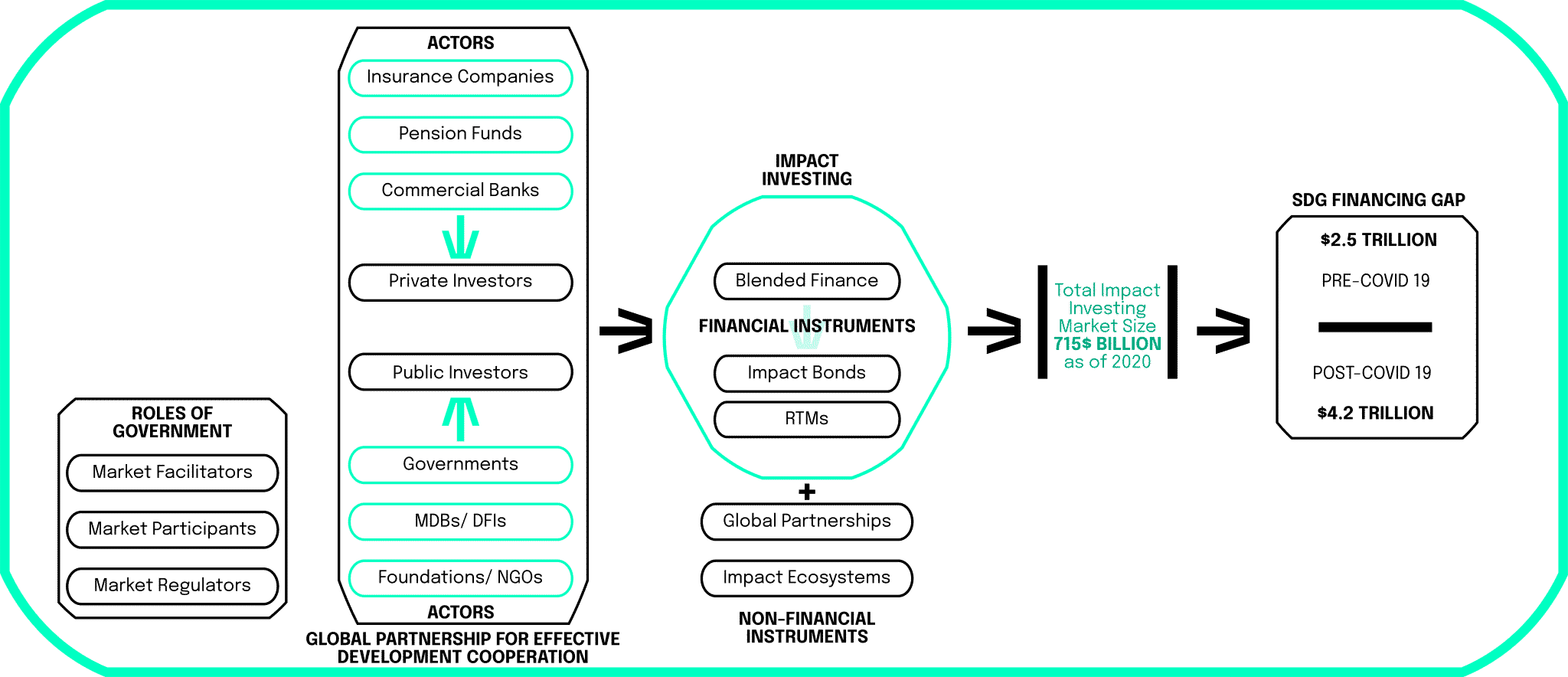

The SDGs adopted by the UN as a call for action for positive change stimulated a new wave of investments within the financial sector. By opening up a new perspective for evaluating the true value of investing, the SDGs turned impact investing, that was once considered a niche, into a widely adopted investment strategy that brings positive financial returns while generating a measurable beneficial impact on the environment and society. At the same time, the aspirational targets underlying the 2030 Agenda require substantial financial investment. Especially given the estimates of an existing funding gap which currently stands at $2.5 trillion (for developing countries alone), the mobilization of private capital is more essential than ever. Impact investing plays a unique role in unlocking that capital. As a result, there is an evident thread tying together SDGs and their actualization through the means of impact investment.

Moreover, the European Union (EU) has been actively playing a role in trying to increase SDG-aligned finance. The EU has made a proposal with the taxonomy to succeed in scaling up the EU’s sustainable investment. This scheme – embedded in the framework of the European Green Deal as well as the action plan on financing sustainable growth – lays out a classification system determining which energy sources can be labeled green for investment purposes. Industries which are less polluting are then labeled sustainable and get access to a certain treatment from banks or investors according to their sustainability rating. However, there are also larger debates about which activities are labeled “green”. The proposed inclusion of certain nuclear and gas activities within the European Union’s list of officially approved “green” investments is set to take effect from2023 after an attempt to block it failed in the European Parliament. This is related to a broader problem when enabling SDG-aligned finance and closing the SDG Financing Gap. Regulators and governments around the world must align individual regulations and frameworks, increasing transparency and accountability, and make regulations easier to understand and implement.

Powered by the investors who are not only driven by financial returns but are also determined to facilitate positive social and environmental impact, impact investing has become a rapidly growing industry. The International Finance Corporation (IFC) report measured the global market for impact investment to have reached the total of $715 billion in 2020. Meanwhile, in 2018 the impact investments worldwide were estimated at a value of $512 billion. The comparison of total estimates reflects a significant increase in investment intensity within the impact investing ecosystem in only two years. However, to increase the scale and effectiveness of impact investing around the world even more, maximizing its contribution towards the global SDG alignment, this innovative branch of investment requires governmental enablement.

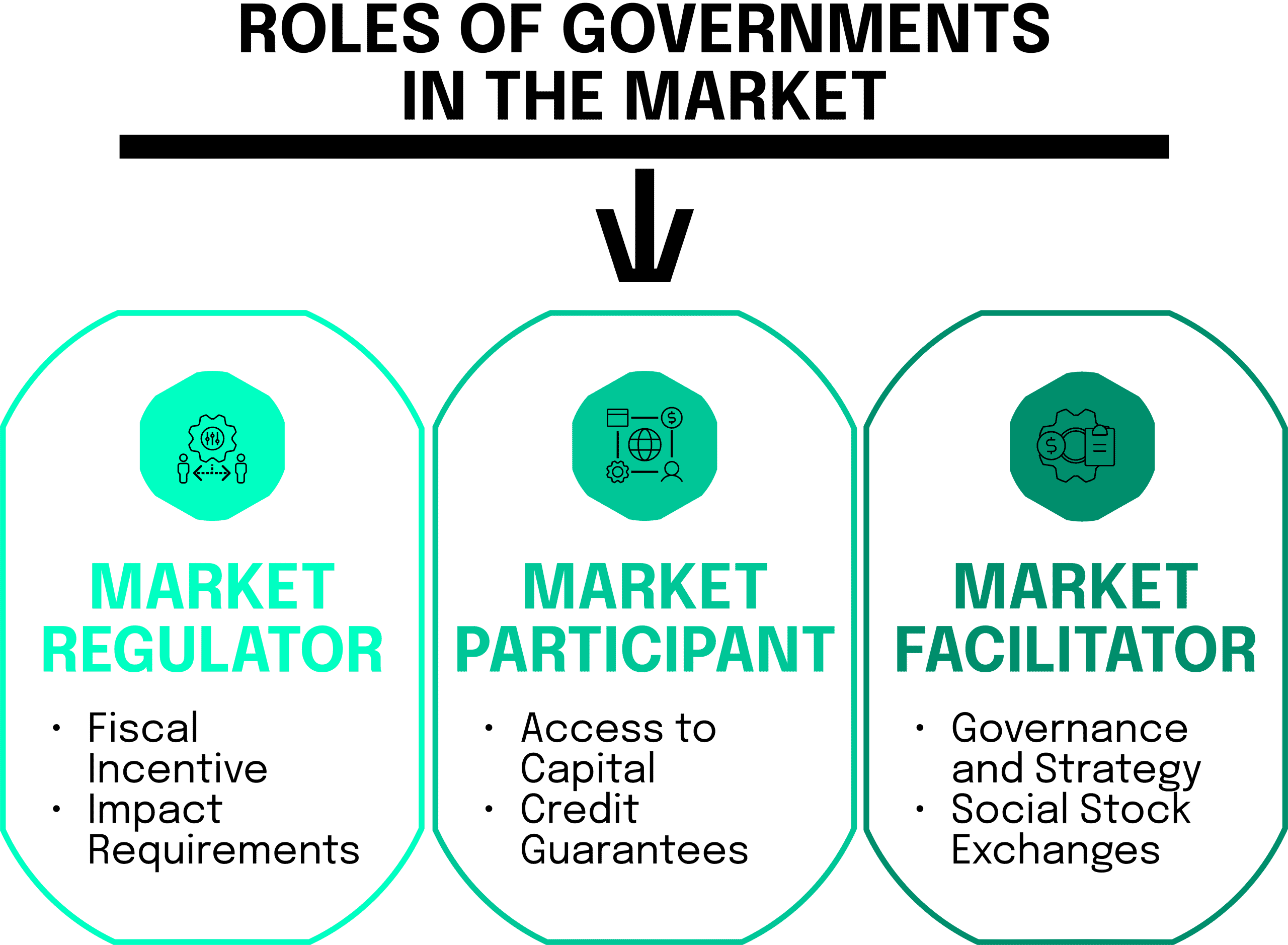

In pursuit of more effective policy outcomes accommodated for sustainable, inclusive economies, governments are taking it upon themselves to act as the catalysts within the impact economy. To stimulate a more favorable environment for impact investing, the governments can act upon three supporting roles, namely market facilitators, regulators, and participants. It is through these roles that governments can strengthen the demand for impact, increase the supply of capital and support market intermediaries.

As market facilitators, governments can support the growth of impact ecosystems by establishing governance bodies, systems, and platforms that enable other actors of the impact-investing markets. In 2018, the United Nations ESCAP (Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific) supported the establishment of the National Advisory Board for Impact Investment in Bangladesh. This dedicated unit within the national government was established with a purpose to set the strategic direction for developing the impact investment ecosystem in the country. Meanwhile, the government of India has been focusing their efforts on the implementation of a novel concept of the social stock exchange, meant to serve the private and non-profit sectors by channeling greater capital to them. This aspirational initiative intends to put in place an electronic platform that will facilitate the linking process between impact investors and social enterprises looking to raise capital. There is a potential for governments to develop and implement a number of beneficial policy tools that could improve the capacity and investment-readiness of impact enterprises, educate and encourage potential impact entrepreneurs and increase the capital available for such entrepreneurs, as shows the example of the Asia-Pacific region.

The regulatory power of government can be leveraged to introduce new regulations and impact requirements that will incentivize more impactful investments. For instance, such incentives have been implemented nationally by the Government of Thailand with the support from ESCAP in the form of a legal framework to stimulate the impact-investing ecosystems across the country and promote social enterprises. The Royal Decree on Tax Exemption, passed in 2016, served as one of the financial incentives for both such enterprises and the organizations that invest in them. One of the key facets of the decree stated that firms that invest in or donate to social enterprises will now be granted a 100% corporate tax exemption. Meanwhile, the Association of Banks in Cambodia joined efforts with the National Bank of Cambodia and the Ministry of Environment to release an initiative that includes mandated safeguards and risk management standards related to social and environmental impacts created by the private sector.

Lastly, governments can participate in markets themselves by providing access to capital to invest alongside private investors. There are few government-backed impact investment funds, but one such example that ESCAP has been supporting is Startup Bangladesh Limited, the flagship and only venture-capital fund sponsored by the Government of Bangladesh. The fund has integrated inclusive and sustainable dimensions by promoting under-represented tech groups and investing in startups that can support the achievement of the SDGs. The fund provides investment in the form of equity, convertible debt and grants in pre-seed, seed and growth-stage startups.

These laws encourage relevant stakeholders by legally recognizing impact enterprises and by providing fiscal and other incentives. Some governments also provide standards for impact measuring and reporting. Governments can help overcome challenges and support the further growth of the impact investment sector. By creating conducive frameworks, adequate legal structures or setting the right incentives, they can also help channel much needed impact capital into social issue areas that have the highest priority in their developmental agendas.

Global partnership for effective development cooperation

When talking about the path to a successful development agenda, it is impossible to not touch upon inclusive global partnerships. Strong international cooperation is the foundation on which the values and principles of SDG alignment are built. The significant economic and human impacts instigated by the COVID-19 pandemic further reflect on that statement. The global crisis amplified the interconnectedness and interdependence of countries and nations around the world. Furthermore, the developing countries appear the most vulnerable in face of such adversity, due to lack of domestic resources and fiscal space to fund adequate response and recovery measures.

SDGs amplify the importance of the transition to Net Zero which in turn requires development and implementation of nature-based solutions (NbS) among other ecosystem-based approaches. Forests are a great example of NbS. Home to 80% of the world’s terrestrial biodiversity, forests provide clean air and water, protect against erosion and landslides, and help to regulate the climate by removing carbon from the atmosphere. By preventing deforestation and degradation, which contribute around 13% of global CO2 emissions, and instead invest in reforestation, we could significantly reduce carbon emissions while staving off the worst impacts of global warming.

Apart from climate change mitigation, transition to NbS as a way to effectively address net-zero targets, entails many other benefits, such as biodiversity conservation, providing drinkable water, enhancing business and job opportunities, and enabling gender equality. According to the G20 report, $120 billion was an estimated investment contributed by the G20 countries in NbS as of 2020. However, to meet the global net-zero targets by 2050, this investment needs to increase four-fold. The total of $536 billion of annual global investment is required, with G20 countries making up for about 40% of that total amount.

The NbS spending gap between G20 and non-G20 countries is caused by the lack of fiscal space and access to global finance preventing non-G20 countries from making sufficient investments. While it has been estimated that non-G20 countries contribute only 20% of the world’s GDP, to meet the global net-zero targets, those regions require 58% of the overall annual NbS investment needs. At the same time, while the G20 countries possess the necessary resources to hit the NbS spending targets, the investments into non-G20 countries prove to be more cost-effective. For instance, the land conversion costs per hectare are significantly higher in G20 countries, compared to the non-G20 group. These positive aspects are good news for enabling NbS spending targets, as lower fixed costs for investments increase the possibility to achieve positive returns on these investments, which ultimately contributes to bridging the existing SDG Financing Gap.

Tackling the challenges that currently hinder the non-G20 countries ability to make sufficient NbS investments, requires all governments to align their post-pandemic economic recovery plans with the global agenda for SDGs. An imperative part of this alignment suggests the repurposing of fiscal policies and trade tariffs in an attempt to scale up financial resources for NbS. G20 countries also play a crucial role in supporting the lower income developing countries when it comes to mobilizing their resources to meet net-zero targets. The public sector, including development finance institutions, is expected to contribute to this process by providing keystone capital towards the nature protection and restoration efforts. The means of such assistance include promotion of nature performance bonds and credit facilities. In addition, putting nature at the heart of the economic, trade and business transition is an essential step to strengthen the NbS investment incentives. The current flow of investment towards NbS led by the private sector amounts for $14 billion, only 11% of the total annual G20 spending. This finding proposes that NbS are mainly perceived as a conservation issue. The responsibility of inciting more private sector investment falls on the governments of the G20 countries, as they have the catalytic power of creating more stable and predictable revenues from ecosystem-centered approaches (e.g. forest carbon).

On a mission to promote nature-positive, cost-effective climate actions, the Natural Climate Solutions Alliance steps up as a NSC (Nature Climate Solution) investment accelerator, as well as a forum for knowledge sharing and technical capacity building, ensuring that nature-based solutions reach their full potential.

The Joint SDG Fund is another initiative that shows how global partnership can facilitate advancement towards Agenda 2030. This wave of financing strategies aims to scale up SDG investment by reinforcing the SDG financing ecosystem, catalyzing strategic investment and unlocking public and private capital. By launching 79 SDG Financing joint programs, the fund introduced a tool that supports implementation of the Addis Ababa Action Agenda (AAAA) at the country level. Referred to as an Integrated National Financing Framework (INFF), the program lays out the full range of domestic and international financing sources of both public and private finance, allowing countries to develop a strategy that aims to increase investment, manage risks and achieve sustainable development priorities, based on their unique national sustainable development strategy. The Joint SDG Fund also strengthens the blended investment portfolio to progressively reach scale in the mobilization of capital for the SDGs. Based on the portfolio overview, in 2021 the catalytic grants that incited de-risking and technical assistance solutions have unlocked $1.45 billion in funding. The joint fund focuses on four main impact areas, namely the blue economy, social impact, food systems and agriculture, as well as energy and climate action.

New ways to finance the SDGs and close the financing gap

Friends of Europe, a Brussels-based, not-for-profit think-tank for European Union policy analysis and debate, held a conference in February 2022, where the members further stretched the discussion about the role of development cooperation. The discussion highlighted the need for new partnership models between development partners and private investors, underlining the increasingly important role of innovative financial instruments.

One of such instruments in particular was introduced by the European Investment Bank (EIB) in 2018. The EIB issues Sustainability Awareness Bonds (SABs) as a complementary extension to pre-existing Climate awareness Bonds with an intention of expanding the impact beyond environmental sustainability and climate change mitigation. Extending their approach to cover the full spectrum of sustainability, EIB made sure that the newly introduced SABs align with the International Capital Market Association (ICMA) Green Bond Principles, Social Bond Principles and Sustainability Bond Guidelines. The issuance of more comprehensive bonds also falls under the Climate Bank Roadmap 2021-2025 that outlines the goals of EIB Group to increase the share of financing dedicated to climate action and environmental sustainability, aligned with the EU Taxonomy regulations.

Furthermore, in light of the SAB Framework released in 2020, UK’s NatWest started monitoring the Sterling market for issuance opportunities for the EIB. After identifying a noticeable surge in interest, particularly from the Central Banks, the NatWest team recommended a launch of an inaugural Sterling Sustainability Awareness Bond for EIB. Introduction of this novel financial instrument in the Sterling market implied an excellent diversification angle for international portfolios.

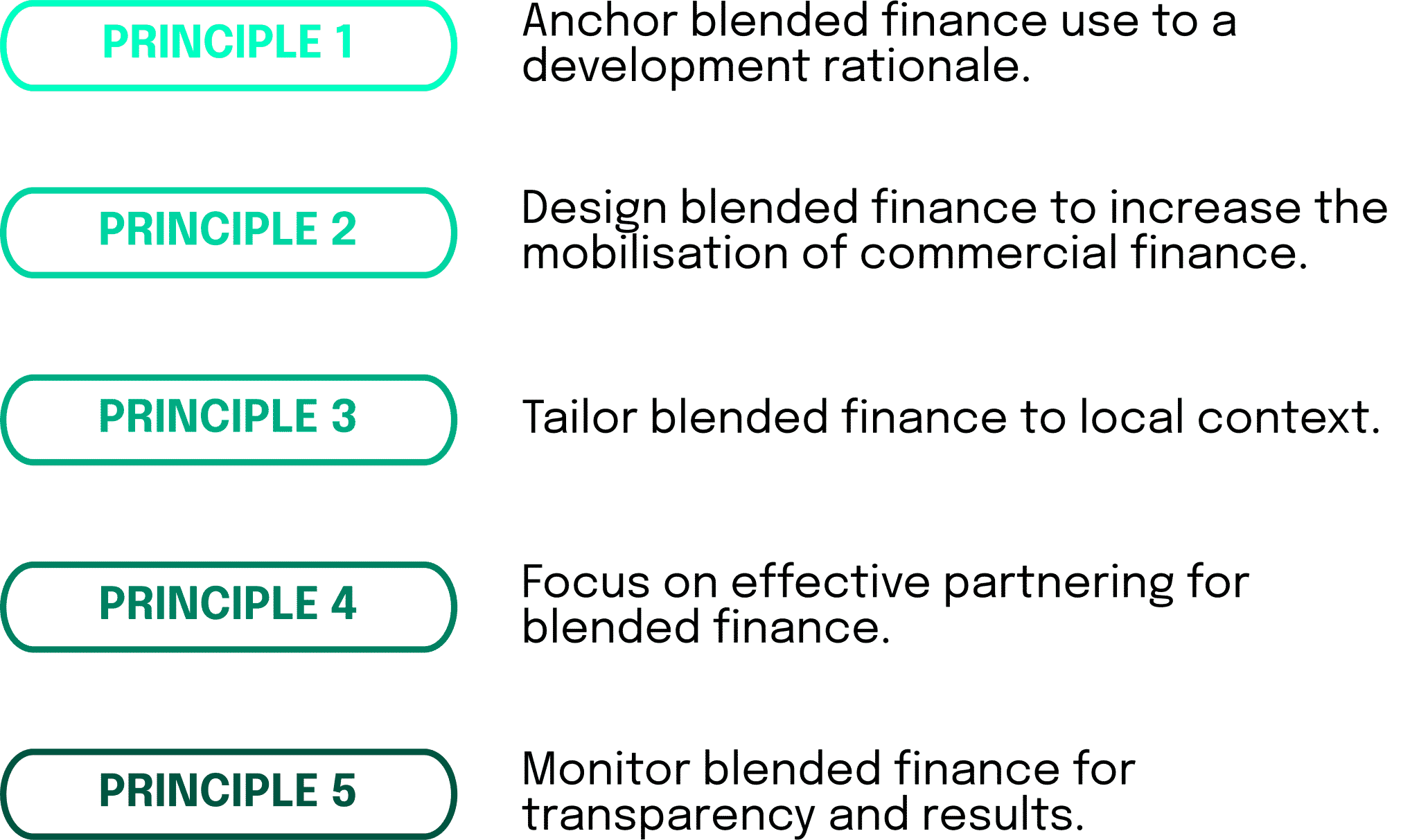

These sustainable awareness bonds are in line with larger financial tools, synthesized under the name of blended finance. Many of the areas in which private investments could have significant impact are considered too risky by private investors. Blended finance has emerged as one of the tools for addressing risks and promoting private investments that can transform people’s lives and contribute toward the SDGs. The International Finance Corporation’s Blended Finance Operations Report highlighted the importance of blended finance instruments for the achievement of the SDGs. Mobilizing commercial investment at the portfolio level can be an effective way to address the needs of small-scale borrowers in developing countries. Risk transfer mechanisms (RTM) can be one effective financial instrument to that effect. IEG found that the blended finance instrument helped set in motion high-risk projects that had potential to generate positive, measurable social and environmental impacts in areas of great need. Such potentially transformative impacts include higher numbers of quality jobs, better and cheaper key products and services for consumers, a dynamic market that can facilitate innovation and entrepreneurship, substantial reductions in greenhouse gas emissions, and a financial return. These impacts could not be achieved otherwise, as the investment projects are deemed too risky for private investors.

Let’s quickly highlight the main risks that make these impactful projects unattractive to investors for a better understanding of blended finance and how this toolbox can generate the needed impact. Some risks to development-focused private sector investment are related to executing a project on time and on budget. In addition, supply chain issues and unstable regulatory and governmental situations make the projects a risky endeavor. Private sector projects aim at achieving returns that are commensurate with the level of risk. That means financiers often demand a risk premium for financing the project, which may make the project vulnerable to external shocks, or require limiting the scope of the project and, thus, not maximizing the benefit that would have resulted from an optimal scale.

So, how does blended finance actually work? Blended finance combines concessional financing, namely loans that are extended on more generous terms than market loans, and commercial funding. The IFC carries out blended finance operations in partnership with donors. Concessional financing supported by donors is combined with IFC and commercial financiers’ regular investments. Thus, taking some risk off private investors while keeping the private market flexibility. This allows the loans to look attractive to private investors as the systematic risk of the loan is lowered through the IFC, leading to lower demanded risk premiums. In return, these lower risk premiums make the loans cheaper for the borrower. Ultimately ending up in more money being available to fund risky, but impactful projects in developing countries. For this to work, the OECD developed five guidelines to establish blended finance as an important tool to promote more commercial financial resources and their usage towards the SDGs. These five guides can be seen in the graph below.

The future of the SDGs

The examples provided in this article highlight the importance of partnerships, shared resources, and global collaboration when it comes to tackling challenges on a global scale. To further harness the potential of SDG alignment, governments have to continue implementing innovative policies that enable and incentivize ecosystems for impact investing. The policymaking for these pioneering initiatives is currently in its infancy, that is why the evaluation of impact of these initiatives should be prioritized to determine the most effective solutions, based on the context and reach of different geographies. The emerging field of innovative financing for SDGs needs to be backed up by continuous policy innovation and reinforcement.

Furthermore, the post-pandemic reality urges governments and investors to support these innovations at the intersection of technology and finance. Continued investment in the digital economy is required, as it plays a critical role in creating a multilateral fintech ecosystem for more inclusive finance and investment. As the world becomes more digital by default, AI-based technologies are becoming increasingly recognized as a solution for potential gaps in enabling sustainable development, addressing transparency, safety and ethical standards. The emergence of AI is shaping an increasing range of sectors, however when it comes to the areas of its influence on the 2030 Agenda, there are some particular connections between AI and SDGs. Research on innovation agenda for zero-emission European cities found that AI can enable smart and low-carbon cities encompassing a range of interconnected technologies such as electrical autonomous vehicles and smart appliances. At the same time, another study on digitalization and energy showed that AI can also help to integrate variable renewables by enabling smart grids. Further societal and economic outcomes linked to the influence of AI show that it can help identify sources of inequality and conflict and potentially reduce those inequalities. For instance, by using simulations to assess how virtual societies may respond to changes.

Meeting the ambitions of the SDGs means building back better not only with sustainability and resilience, but also with a greater emphasis on inclusivity, equality, and equity. While all the goals of the 2030 Agenda are linked and interdependent, this article has already stretched the critical role played by the private sector in achieving those goals, with the UN emphasizing that business cannot thrive unless people and planet are thriving. The practical guide for companies created by the UN Global Compact identifies how to use the SDGs as a template for a new way of business.

Investing in SDGs – what is the potential outcome?

What is the potential outcome when closing the SDG Financing Gap? Results can have much broader implications than just an environmental and social impact. We will highlight the potential benefits of closing the SDG Financing Gap by looking at SDG 5 that aims to achieve gender equality and empower all women. Advancing women means advancing equality for all, as further proven by the McKinsey findings, suggesting that what is good for gender equality is good for the economy and society as well. Their study found that acting to advance gender equality could add a staggering $13 trillion to global GDP by 2030. Goal Five is seen as pivotal succeeding planning, there is undeniable evidence showing the linkage between gender equality and ESG Performance. A paper by Harvard Law School on Corporate Governance found that bringing more women into leadership roles opens a new source of talent that is more representative of the general workforce and society. The female leaders have the potential of bringing fresh and diverse perspectives to complex issues. From the business performance standpoint, extensive research shows that organizations with a higher percentage of women in leadership positions benefit from better performance, greater market share, and increased financial returns. When working through the framework of SDGs, leaders, businesses, and individuals have to focus on building a sustainable future that fosters diversity, inclusivity, and equality. That is why a big factor underlying the future success of SDGs involves empowering women entrepreneurs and scaling up investments directed to women-run businesses exponentially.

Avramenko, E. (2022, April 5). Universal milestone: the Global Impact Investing Network’s

approach to assessing social impact. Positive Changes, 2(1), 22–43.

https://doi.org/10.55140/2782-5817-2022-2-1-22-43

Barua, S. (2019, December 18). Financing sustainable development goals: A review of

challenges and mitigation strategies. BUSINESS STRATEGY &Amp;

DEVELOPMENT, 3(3), 277–293. https://doi.org/10.1002/bsd2.94

Choi, E., & Seiger, A. (2020). Catalyzing Capital for the Transition toward Decarbonization:

Blended Finance and Its Way Forward. SSRN Electronic Journal.

https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3627858

European Commission. (2018, March 8). Renewed sustainable finance strategy and

implementation of the action plan on financing sustainable growth. Retrieved

September 4, 2022, from https://finance.ec.europa.eu/publications/renewed-

sustainable-finance-strategy-and-implementation-action-plan-financing-sustainable-

growth_en

European Commission. (2019, October 12). European Green Deal. Retrieved September 2,

2022, from https://ec.europa.eu/info/strategy/priorities-2019-2024/european-green-

deal_en

Franco, I. B., & Abe, M. (2019, November 14). SDG 17 Partnerships for the Goals. Science

for Sustainable Societies, 275–293. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-32-9927-6_18

Havemann, T., Negra, C., & Werneck, F. (2020, July 27). Blended finance for agriculture:

exploring the constraints and possibilities of combining financial instruments for

sustainable transitions. Agriculture and Human Values, 37(4), 1281–1292.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10460-020-10131-8

Hutton, G. (2022). SDG 6 global financing needs and capacities to ensure access to water and

sanitation for all. Financing Investment in Water Security, 151–175.

https://doi.org/10.1016/b978-0-12-822847-0.00001-6

Kriese, M. (2021, July 16). The Role of Formal and Informal Finance in Economic

Development. Journal of Economics, Finance and Management Studies, 04(07).

https://doi.org/10.47191/jefms/v4-i7-17

Lafortune, G., Fuller, G., Schmidt-Traub, G., & Kroll, C. (2020, September 17). How Is

Progress towards the Sustainable Development Goals Measured? Comparing Four

Approaches for the EU. Sustainability, 12(18), 7675.

https://doi.org/10.3390/su12187675

Lagoarde-Segot, T. (2020, April 1). Financing the Sustainable Development Goals.

Sustainability, 12(7), 2775. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12072775

Shalneva, M., Malofeev*, S., & Zinchenko, Y. V. (2019, March 20). Sustainable Finance As

A Way Of Transition Of Companies To Green Economy. The European Proceedings

of Social and Behavioural Sciences. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2019.03.45

Ziolo, M., Bak, I., & Cheba, K. (2020, December 3). THE ROLE OF SUSTAINABLE

FINANCE IN ACHIEVING SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT GOALS: DOES IT

WORK? Technological and Economic Development of Economy, 27(1), 45–70.

https://doi.org/10.3846/tede.2020.13863

neosfer GmbH

Eschersheimer Landstr 6

60322 Frankfurt am Main

Teil der Commerzbank Gruppe

+49 69 71 91 38 7 – 0 info@neosfer.de presse@neosfer.de bewerbung@neosfer.de