15min reading time

Before we start diving into the depths of the Sustainable Finance universe, we need a clear definition. So what exactly is Sustainable Finance anyway? The European Commission defines Sustainable Finance as the process of integrating environmental, social and governance (ESG) considerations into investment decisions in the financial sector, leading to more long-term investments in sustainable economic activities and projects.

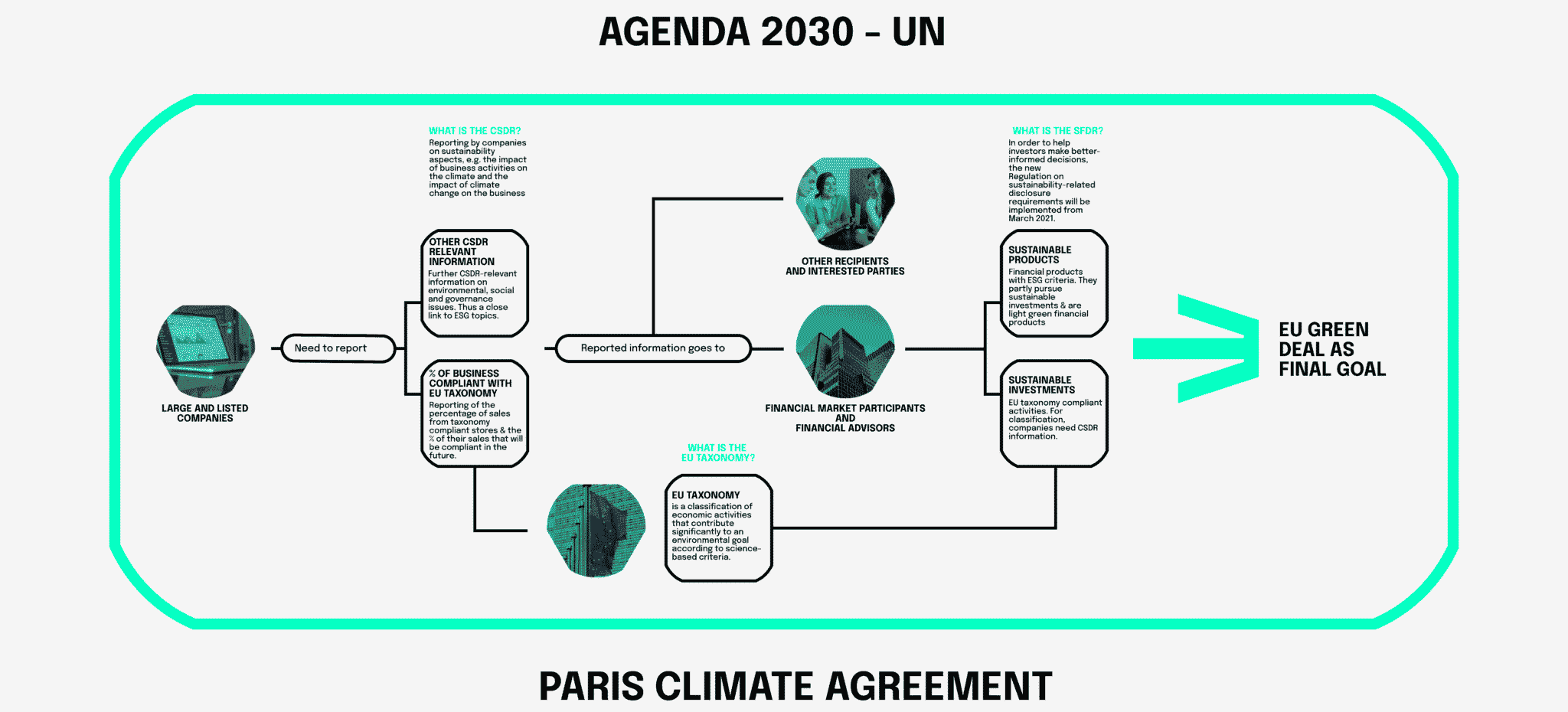

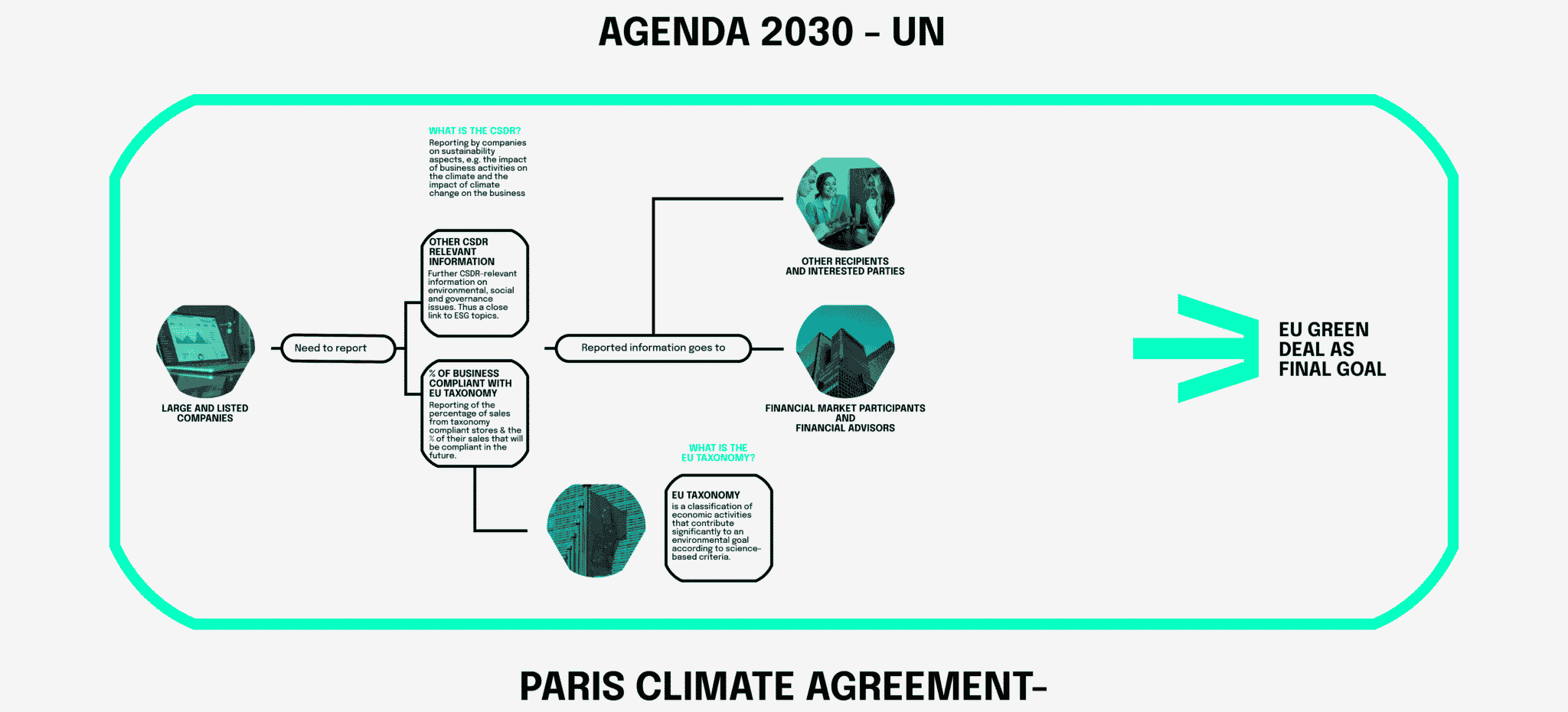

However, as many practices, terms, regulations and sustainability approaches have been established over the years, the aim of this article is to bring clarity to the various issues. We first define the EU-wide regulations and relate them to each other. The focus here is on the European Green Deal, the EU Taxonomy, the Corporate Sustainable Reporting Directive, CSRD for short, and the Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (SFDR). In addition, in the second part of the article, we look at how the private financial sector has so far considered the ESG considerations addressed and how these are linked to overarching sustainable development goals. Here, we primarily highlight ESG investing as the best-known sustainable investment strategy, but will also introduce impact investing as one of the newest investment strategies.

Where did everything start?

Agenda 2030

On September 25, 2015, the UN General Assembly adopted a new global framework for sustainable development: the 2030 Agenda. It provides the global framework for environment and development policy in the coming years. At the heart of the Agenda are the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) with their 169 targets. The SDGs cover the three dimensions of sustainability: economic, social and environmental. They touch on all policy areas, from economic, social, environmental and financial policy, to agricultural and consumer policy, to areas such as transport, urban planning, education and health. These goals address all countries of the world and are not aimed solely at the Global South, as previous development goals did. This was tantamount to a paradigm shift aimed at achieving a sustainable transformation toward an economic and social system that is fair for the future.

Paris Climate Agreement

In 2015, another landmark agreement was signed. The Paris Climate Agreement sets out a global framework for limiting climate change by aiming to limit global warming to well below 2 °C and continuing efforts to limit it to 1.5 °C. The EU and its member states are among nearly 190 parties to the Paris Agreement. The agreement is the first universal, legally binding global climate change agreement.

The 2030 Agenda and the Paris Climate Agreement provide the framework within which various EU-wide regulations have been formed. The Paris Climate Agreement and Agenda 2030 also set the tone for the EU when it comes to new legislation and how it must be aligned with global development goals.

The EU and sustainable financial regulation

Now that we have defined the broad framework for the legislation of the future, we can turn to the regulatory side. EU regulations are intended to promote sustainable investment and accelerate the transformation to a sustainable financial economy. In recent years, the European Central Bank and the European Commission have emerged as key legislators with the common goal of making the economy and the financial sector more sustainable.

European Green Deal

As the first major operationalization of the 2030 Agenda and the Paris Climate Agreement, we consider the European Green Deal. This policy initiative sets the tone for the EU-wide policy landscape of the coming years and decades by concretizing the goals of the 2030 Agenda and the Paris Climate Agreement and translating them into precise EU targets.

On December 11, 2019, the Commission published its Communication on the European Green Deal. The Green Deal is a bundle of policy initiatives aimed at several environmental goals, including a carbon-neutral Europe by 2050. The EU has also committed to mobilize at least €1 trillion in sustainable investments over the next decade.

The Green Deal has several focus points, which we will briefly list here, and which are closely linked to the SDGs and ESG criteria:

- Climate policy

- Clean energy

- Sustainable industries

- Sustainable mobility

- Elimination of created pollution

- Preservation of biodiversity

- Sustainable research and develop

At the same time, the Commission is also putting pressure on private companies to invest more in sustainable projects. The first measures for Sustainable Finance are defined here. These measures are effective in boosting private sector investment in green and sustainable projects. Here, the Green Deal identifies three key points for a new Sustainable Finance strategy. The taxonomy, for classifying environmentally sustainable activities, is seen as a central element. In addition, sustainability is to be integrated more strongly into the framework of corporate management. The second central element is to offer retail investors, investors, and companies easier opportunities for sustainable investments through clearer labeling. The third major element is to manage climate and environmental risks and integrate them into the financial system. This point aims at better integrating risks into prudential regulations and assessing the suitability of capital requirements for green investments.

But how will the Green Deal be financed? The proposed financing is set out in the EU Investment Plan for the Green Deal. It comprises two main funding streams totaling €1 trillion. Over half of the budget, €528 billion, will come directly from the EU budget and the EU Emissions Trading Scheme. The remainder will be raised through the InvestEU program, which includes €279 billion from the public and private sectors and €114 billion from national co-financing up to 2030. The European Innovation Council has also allocated a budget of €300 million to invest in market-creating innovations that contribute to the goals of the EU Green Deal. These expanded measures will contribute to the European Green Deal by boosting private sector investment in green and sustainable projects and reducing investment risk.

We understand the European Green Deal to be the EU’s final goal of climate neutrality by 2050, and all the other EU-wide regulations we will learn about later in this article share the goal of insuring climate neutrality. They are all based on the Green Deal and the three building blocks implemented there for the EU’s new Sustainable Finance Strategy.

The EU Taxonomy

As we have just seen, one of the most important building blocks of the European Green Deal is Sustainable Finance. It was already clear in the introduction that this term is not a concrete strategy, but that this buzzword results in different investment strategies with different guidelines and criteria. But also the national legislators implement Sustainable Finance in different statutes. This is exactly where the EU steps in and defines the term Sustainable Finance in more detail with the EU Taxonomy. Thus, the taxonomy specifies exactly which economic activities will be considered sustainable in the future. This will steer all companies towards a more sustainable economic system. In the future, companies will then have to report on the percentage of all their business activities that are sustainable. This reporting obligation will also make it easier for financial institutions and investors to invest in sustainable projects and companies. Thus, the EU taxonomy ensures that one of the central building blocks of the Sustainable Finance Strategy can be achieved and investment decisions can be made more transparently.

Nevertheless, it is important to understand that the EU Taxonomy is not a set of standards to be implemented. Rather, it provides a framework for regulators and legislators in the EU to assess their own regulatory obligations in the context of broader global initiatives. However, because the taxonomy includes some standards, it also provides guidance on how to apply existing standards in a way that is consistent with EU law. Most notably, as briefly touched on above, it includes comprehensive reporting requirements for companies and the financial sector.

Overall, we can see the EU Taxonomy as tightening up the concept of Sustainable Finance. The taxonomy will help to achieve the overarching goals set out and defined in the Green Deal. Both frameworks will thus together assure that the European financial sector and the entire European economy must act in a more sustainable way.

The Taxonomy Regulation applies to the financial sector and companies that are required to publish a non-financial statement at company or group level. The EU rules on non-financial reporting currently apply to large companies and public interest entities with more than 500 employees. This affects around 11,700 large companies and groups in the EU. From January 1, 2023, all large companies will then have to report their taxonomy adjustment along with relevant information that can help investors assess their ESG performance.

Corporate Sustainable Reporting Directive

As we explained in the last section, the EU Taxonomy is a framework for government agencies that, as a first step, more narrowly defines the term Sustainable Finance. In addition, the Taxonomy will link EU financial regulation even more closely to the 2030 Agenda and the Paris Climate Agreement. Since the taxonomy is seen as a framework, it requires concrete regulation that is prescribed by the EU and finds its direct application in the European economy.

The Corporate Sustainable Reporting Directive, CSRD for short, will entirely change the reporting requirements of many companies in Europe and can be understood as one of the operationalization of the EU Taxonomy. The focus of the EU’s legal requirements for corporate sustainability reporting has so far been the so-called Non-Financial Reporting Directive (NFRD), or CSR Directive. However, this only applies to capital market-oriented companies with more than 500 employees. The NFRD requires these companies to disclose non-financial information in a so-called non-financial report.

According to the NFRD Directive (Directive 2014/95/EU), large listed companies, banks, and insurance companies with more than 500 employees must publish reports on the measures they have implemented regarding the following:

- Environmental protection

- Social responsibility and treatment of employees

- respect for human rights

- combating corruption and bribery

- Diversity on company boards (in terms of age, gender, education and professional background)

The CSRD is the planned renewal, re-sharpening and replacement of the old NFRD directive. The new directive will include significantly more companies in the reporting obligation for their ESG activities.

The CSRD is currently still at the proposal stage and is being discussed in the European Parliament and Council. It would extend the current scope of non-financial reporting requirements to all large companies, regardless of their capital market orientation. This would then include all companies that meet two of the following three criteria: more than 250 employees, total assets of more than €20 million or sales of more than €40 million. This would mean that nearly 50,000 companies in the EU would have to follow detailed sustainability reporting standards, an increase from the 11,000 companies subject to the current requirements.

The Commission also proposes the development of standards for large companies and separate, appropriate standards for SMEs that can be applied voluntarily.

Overall, the proposal aims to ensure that companies provide reliable and comparable sustainability information that is required by investors and other stakeholders. This would facilitate a transparent and simplified flow of sustainability information through the financial system. Furthermore, the content of reporting on sustainability aspects is to be defined more concretely and comprehensively via separate EU Sustainability Reporting Standards.

Sustainable finance disclosure regulation

If we think further about the reporting chain just described, the various financial institutions within the EU must of course also report on their activities. Here, too, the European Commission has issued a new regulation that will have a significant impact on the European financial sector.

The Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (SFDR) is a regulation on the disclosure of sustainable financial products to improve transparency in the market for sustainable investment products, prevent greenwashing, and increase the transparency of sustainability statements by financial institutions.

The SFDR specifies that these financial firms must disclose to customers the extent to which they incorporate sustainability factors into the decision-making process for their financial products and what the material adverse sustainability impacts of their financial products are.

The SFDR aims to create a level playing field for financial market participants and financial advisors in terms of transparency regarding sustainability risks, consideration of adverse sustainability impacts in their investment processes, and provision of sustainability-related information in relation to financial products. The SFDR requires asset managers to provide prescribed and standardized disclosures on how ESG factors are integrated at both the firm and product levels. A significant portion of the SFDR applies to all asset managers, whether or not they have an explicit ESG or sustainability focus. The SFDR manifest themselves in additional disclosures for financial market participants on their websites, in prospectuses and periodic reporting.

Thus, the SFDR completes our overview of EU-wide regulations with the common goal of achieving the EU Green Deal. Together with the CSRD, it ensures that information regarding sustainability and ESG criteria is produced and published in a more transparent and comparable manner in the private sector. This will enable retail investors and financial institutions to make better investment decisions and to invest more consciously and safely in sustainable projects.

Learnings aus diesem Artikel

As explained, the EU Taxonomy, CSRD and SFDR are part of a larger EU Sustainable Finance Framework that embeds sustainability factors at various levels of the economy. This framework, the new regulations and reporting rules should be understood in the larger context of the European Green Deal and the UN’s 2030 Agenda. Thus, the overarching goals of European climate neutrality by 2050 and achieving the SDGs are to be given the highest priority.

So, overall, we see that the issue of Sustainable Finance is strongly influencing legislators. At the same time, however, it also becomes clear how interconnected and complex the current legislative situation in Europe is and that individual regulations must always be considered in conjunction with overarching frameworks.

In the following article, we will take a closer look at the effects of the framework and, in particular, take a critical look at investment strategies.

Arsova, S., Corpakis, D., Genovese, A. & Ketikidis, P. H. (2021). The EU green deal: Spreading or concentrating prosperity? Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 171, 105637. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2021.105637

Ashraf, N. & Bandiera, O. (2017). Altruistic Capital. American Economic Review, 107(5), 70–75. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.p20171097

Clark, C., Lalit, H. & Rockefeller Capital Management. (2021, 8. Oktober). ESG Improvers: An Alpha Enhancing Factor. Rockefeller Capital Management. Abgerufen am 16. März 2022, von https://rcm.rockco.com/insights_item/esg-improvers-an-alpha-enhancing-factor/

Clark, G. L. (2005). Money flows like mercury: the geography of global finance. Geografiska Annaler: Series B, Human Geography, 87(2), 99–112. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0435-3684.2005.00185.x

Cozier, M. (2017). The US withdrawal from the Paris Agreement: a global perspective. Greenhouse Gases: Science and Technology, 7(5), 774–777. https://doi.org/10.1002/ghg.1736

Giacomelli, A. (2022). EU Sustainability Taxonomy for Non-financial Undertakings: Summary Reporting Criteria and Extension to SMEs. SSRN Electronic Journal. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4012636

GSI Alliance. (2021, 1. Januar). GLOBAL SUSTAINABLE INVESTMENT REVIEW 2020. http://www.Gsi-Alliance.Org/. Abgerufen am 8. März 2022, von http://www.gsi-alliance.org/

Hainsch, K., Löffler, K., Burandt, T., Auer, H., Crespo Del Granado, P., Pisciella, P. & Zwickl-Bernhard, S. (2022). Energy transition scenarios: What policies, societal attitudes, and technology developments will realize the EU Green Deal? Energy, 239, 122067. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2021.122067

International Energy Agency. (2022, 8. März). Global CO2 emissions rebounded to their highest level in history in 2021 – News. IEA. Abgerufen am 16. März 2022, von https://www.iea.org/news/global-co2-emissions-rebounded-to-their-highest-level-in-history-in-2021

Khan, M., Serafeim, G. & Yoon, A. (2016). Corporate Sustainability: First Evidence on Materiality. The Accounting Review, 91(6), 1697–1724. https://doi.org/10.2308/accr-51383

Maule, S. & Egli, F. (2017, 21. März). Missing in Action – The lack of ESG capacity at leading investors. E3G. Abgerufen am 10. März 2022, von https://www.e3g.org/publications/missing-in-action-the-lack-of-esg-capacity-at-leading-investors/

Och, M. (2020). Sustainable Finance and the EU Taxonomy Regulation – Hype or Hope? SSRN Electronic Journal. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3738255

Pacces, A. M. (2021). Will the EU Taxonomy Regulation Foster Sustainable Corporate Governance? Sustainability, 13(21), 12316. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132112316

The Paris agreement on Global Climate change cannot be fully enforced, because this is an incomplete agreement. (2020). Earth & Environmental Science Research & Reviews, 3(2). https://doi.org/10.33140/eesrr.03.02.11

PRI. (2017, 12. Oktober). The SDG investment case. Abgerufen am 10. März 2022, von https://www.unpri.org/sustainable-development-goals/the-sdg-investment-case/303.article

Puaschunder, J. M. (2016). On the Emergence, Current State and Future Perspectives of Socially Responsible Investment (SRI). SSRN Electronic Journal. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2720686

Rivas, S., Urraca, R., Bertoldi, P. & Thiel, C. (2021). Towards the EU Green Deal: Local key factors to achieve ambitious 2030 climate targets. Journal of Cleaner Production, 320, 128878. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.128878

Tóthová, D. (2022). Measuring the Environmental Sustainability of 2030 Agenda 2030 Implementation in EU Countries: How Different Assessment Methods Affect Results? SSRN Electronic Journal. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4025884

United Nations. (2017, 17. Oktober). The SDG investment case. PRI. Abgerufen am 16. März 2022, von https://www.unpri.org/sustainable-development-goals/the-sdg-investment-case/303.article

- Geschäftsführer neosfer

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consetetur sadipscing elitr, sed diam nonumy eirmod tempor invidunt ut labore et dolore magna aliquyam erat, sed diam voluptua. At vero eos et accusam et justo duo dolores et ea rebum. Stet clita kasd gubergren, no sea takimata sanctus est Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet. Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet,

These might interesst you

Further News

neosfer GmbH

Eschersheimer Landstr 6

60322 Frankfurt am Main

Teil der Commerzbank Gruppe

+49 69 71 91 38 7 – 0 info@neosfer.de presse@neosfer.de bewerbung@neosfer.de