20min reading time

Introduction

People, prosperity, planet, partnerships, and peace – the five critical elements defined by the UN as the pillars of the 2030 Agenda. On the quest of addressing the collective challenge to transition from a carbon-fueled past to a cleaner, more sustainable future, the 5Ps marked the inception of 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in 2015. As the core of the 2030 Agenda, the SDGs were intended as guidelines for all global, regional and national development endeavors to follow for the next 15 years. Achieving these ambitious goals is highly dependent on the resources needed to fund the grand mission. The concept of finance for development has birthed the idea of financing for the SDGs. As a roadmap to follow, the Addis Ababa Action Agenda (AAAA) defined the global framework for development finance.

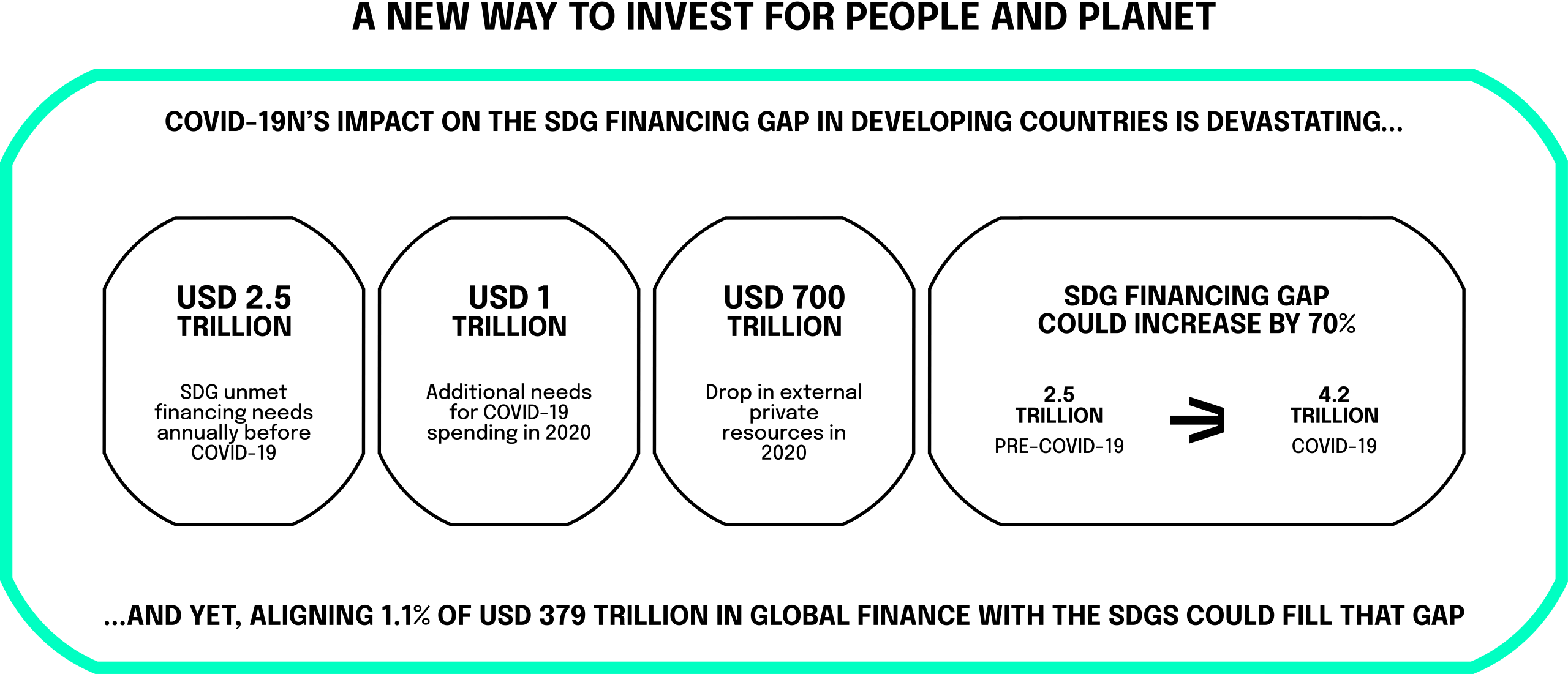

However, since the roadmap for sustainable development was established, there has been a breach between financial resources devoted to the cause of the 2030 Agenda and the actual amounts needed to deliver the defined SDGs. The chasm, referred to as the SDG financing gap, has been estimated at $2.5 trillion by the International Finance Corporation (IFC). The COVID-19 pandemic has only further amplified this financing rift. Mainly due to the consecutive effect of decrease in resources against the increasing needs, the OECD revised the annual financing gap to have expanded by $1.7 trillion. Overall, the social and economic shocks of the pandemic emphasized the urgent nature of SDGs, as the crises pointed towards the global interdependencies and disproportions. The phenomenon responsible for the issues that particularly impact the emerging economies, including the insufficient portion of financial commitments made towards developing countries.

The urgency sparked by the economic and social crisis, along with the previously existing financing gap raise an inevitable question – how to refine the methods of addressing the finance breach and unlock the sufficient resources for long-term SDG funding and alignment? Most research findings claim the answer lies within the financial sector, as it plays the key role in offering innovative financing instruments. Mobilizing capital and leveraging private sector funding for sustainable development are necessary steps on the way to fostering a multi-stakeholder approach that addresses the interconnectedness of global issues.

The Challenges on the way to SDG aligned finance

Impact of Covid-19 on the financing gap

The global outlook on the damage caused by the pandemic in respect to the SDG financing and alignment not only reflects on short-term collapse in funding resources, but emphasizes bigger concerns. The coronavirus outbreak became a turning point in addressing the challenges of the global sustainable development agenda, as it reinforces the very basis which SDGs are based on. The interrelated nature of these goals essentially conveys the fundamental truth of the world being an interconnected system, creating a threat of systematic failure as a result of uncoordinated alignment in addressing the sustainability agenda. The issue of international cooperation has been clearly highlighted by the pandemic, as the 2020 record showed a decline of $700 billion in external financing sourced to developing countries, reflecting that most countries turned inward to protect their citizens and economies in response to the global crisis.

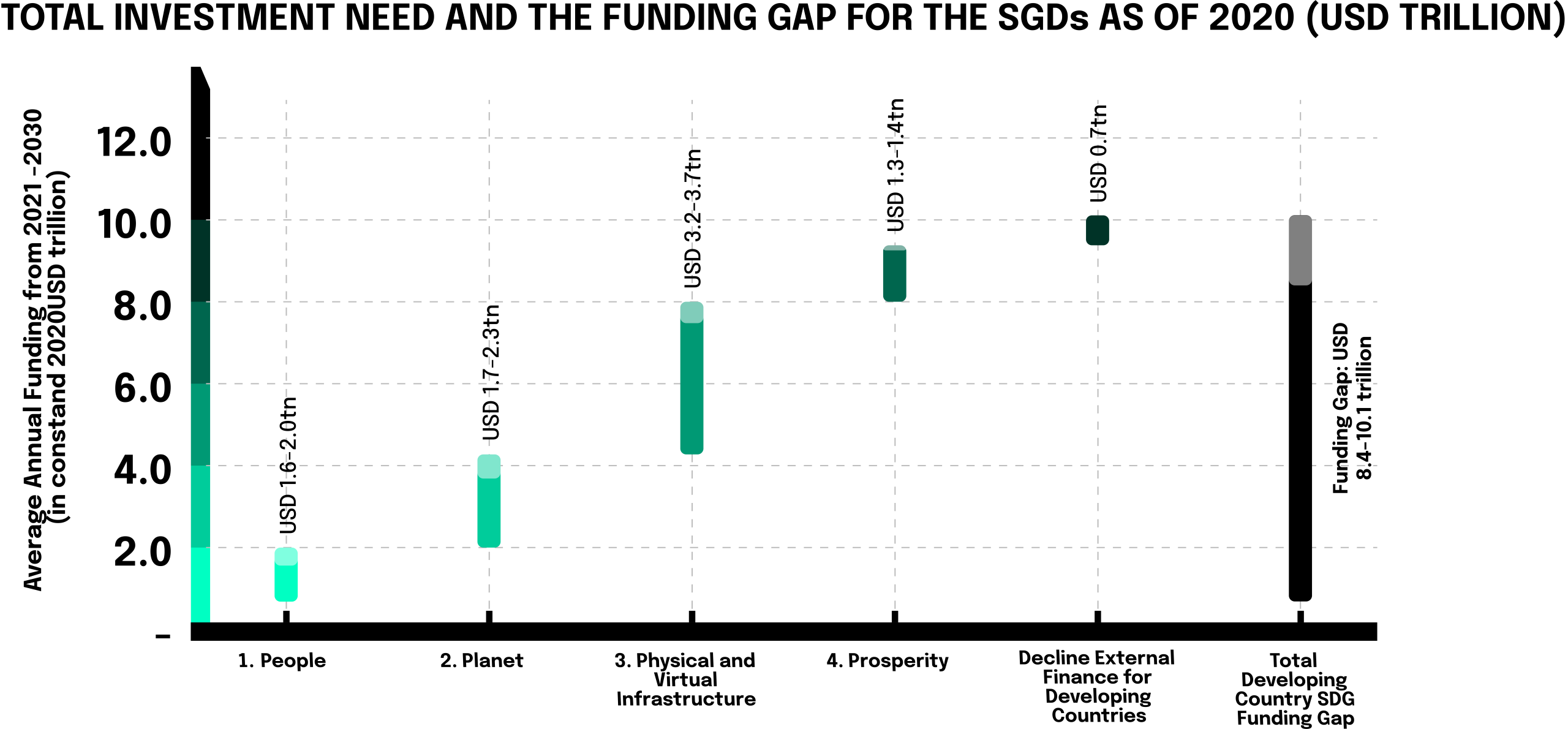

The Force of Good Report estimated that 10% of the global GDP would be required annually to close the current financing gap which now amounts to a total of $116-$142 trillion. With another $80 trillion that would have to be added on top of an already insurmountable financial obstacle, if counting the costs for energy transition needed for climate change. With the transition funding added to the overall costs of SDGs through 2050, the calculations comprise a total of $200-220 trillion in required finance. As these total numbers are extremely hard to grasp, with the next graphic we want to take a step back and take it to the annual level. Currently, there is only around $4 billion annually invested into the SDGs. Considering the new development of the pandemic’s impact, we split the newest annual funding gap into four big drivers and highlight the overall funding requirements to achieve the SDGs.

Impact of geopolitical tension on the financing gap

The slow progress on fulfilling the financing needs for the Sustainable Development Agenda has been framed by several constraints. Namely, intensified geopolitical tensions surrounding trade and technology, increasing external debt amidst unresolved systemic issues, misalignment in collaboration for development finance between public and private sectors.

International trade has moved away from the sustainable development agenda, as lately the world has witnessed solitary interest-centered actions, trade tensions and gate-keeping measures. Under the circumstances of continuous technological war between China and US, as well as the Brexit agreement that fully came into effect in 2020, previously existing commitments to SDG–friendly international trade were impeded. Amidst the trade war, persistent inequalities and disproportionate benefits of globalization are stripping developing countries of a chance to equally participate in the global trading scenery. Despite the initial bid on favorable development results related to technology transfer and shared industrial policies, the notion of international trade has been heavily weaponized. The rising US-China tariffs amidst the ongoing tensions puts at risk the industries in developing countries that are closely integrated into Chinese and American supply chains. At the same time, the departure of the UK from the EU and the consequent adjustment of their trade policy changed the trajectory of many emerging markets, as well as the global economy overall. The reduction in EU exports as a result of lost preferential access to the UK market was estimated at $35 billion per year, according to UNCTAD. The collateral damage also affects the competitiveness of many non-EU developing countries, measured in their exports to the UK market. Those countries include Cambodia (-12%), Madagascar (-14%), Mozambique (-32%), Myanmar (-12%) and Nepal (-20%).

Impact of badly defined framework on the financing gap

A poorly defined framework creates risks of SDG washing, as even ESG criteria that are more widely recognized among investors have been heavily criticized. One of the recent studies analyzed the records of U.S. companies listed in both ESG and non-ESG fund portfolios. The comparative research found the companies added in the ESG portfolios to have showcased worse compliance with both labor and environmental criteria. The results of the study also stated that the ESG portfolio-listed companies did not subsequently improve their performance regarding any of the mentioned regulations. This shows that the equities and bonds of the companies claiming their place in the ESG fund portfolios might not be going through such stringent testing after all. At the same time, the European Corporate Governance Institute took a look at 684 U.S. institutional investors that signed the UN’s Principles of Responsible Investment (PRI) and the respective ESG scores of the companies they have invested in. That research showed no improvement in the scores of companies supported by PRI signatories compared to those held by the institutional investors that had not signed the PRI.

Why do ESG funds perform so badly? The answer might appear quite expected, as the misalignment between public and private sectors’ approach towards achievement of SDGs results in lack of proper regulations and accountability surrounding the business. The evidence suggests that companies cover up their poor business performance by publicly embracing their ESG focus. When the earnings expectations turn out underperformed, the ESG comes in as a convenient excuse for the managers to shift the attention from their insufficient results. As a result of this phenomenon, many sustainable fund managers fall for the trap of allocating their investments into underperforming companies that proclaim misleading commitment to ESG.

Other more complete frameworks, such as the EU taxonomy, ensure a contribution to environmental objectives, yet still fail to cover all the aspects of sustainable development. When applying sustainable taxonomies, asset managers frequently encounter challenges such as taxonomy fragmentation and lack of transition taxonomies. As national taxonomies develop, multinational asset managers face discrepancies between expectations and requirements when applying those frameworks to operations in different jurisdictions. With the risk that the “green” criteria met by one taxonomy does not necessarily suffice the same criteria for another, there is a need for more broadly applicable frameworks. The improved framework would have to be appropriately tailored to the circumstances and regulations of the local standard.

Impact of missing transition taxonomies on the financing gap

Such incoherence is further intensified by the lack of transition taxonomies. This classification of a taxonomy, commonly referred to as “brown”, significantly differs from the green framework approach. While the EU’s ‘green’ taxonomy defines the threshold for sustainable economic activities, the brown taxonomy is part of the EU’s consultation on a Renewed Sustainable Finance Strategy. Its purpose is to help incentivize companies operating in so-called “brown” sectors like oil and gas to shift toward greener practices. The brown taxonomy would list activities deemed as environmentally harmful, rather than the green taxonomy that emphasizes sustainable economic activities. A brown taxonomy is estimated to have greater credit implications due to newly defined disincentive policies such as higher prudential capital requirements. The relevance could be observed in the example of asset managers and banks applying its classification as exclusion criteria in respect to their investment considerations.

Another potential impact of brown taxonomy relates to how investors identify and assess environmentally harmful companies based on the ESG-integrated investment frameworks. The greater standardization in the evaluation that can be achieved through brown taxonomy could solve the issues of transparency and accountability regarding ESG compliance previously mentioned in the article. If asset managers were to apply this exclusionary criteria in their assessment, the corporations would face more strict screening and radical consequences, regardless of being labeled as ESG-compliant.

The above-mentioned information asymmetries that underlie SDG washing exist within the agenda as a result of the confusion surrounding the standards on sustainable finance. Terms like “sustainable”, “responsible” and “SDG-aligned”, applied to describe criteria for investments, are used so loosely that it becomes challenging to navigate the landscape. Inconsistent measurement and metrics systems, ambiguous perspectives and vaguely defined terminology compose a fragmented approach to the SDG agenda, causing its actors to appear unaligned.

Finally, frameworks ensuring impact, especially in the impact investing industry are demanding but are constraining and costly and therefore drag a few investors. We need to trade off market acceptance against quality of financing. As it has been shown, there are already many standards globally, which is why improving existing ones (which already possess the organizational structure and could be geographically expanded), rather than establishing many new ones, should be considered. Political appetite will also determine the depth and breadth of financing trying to shift.

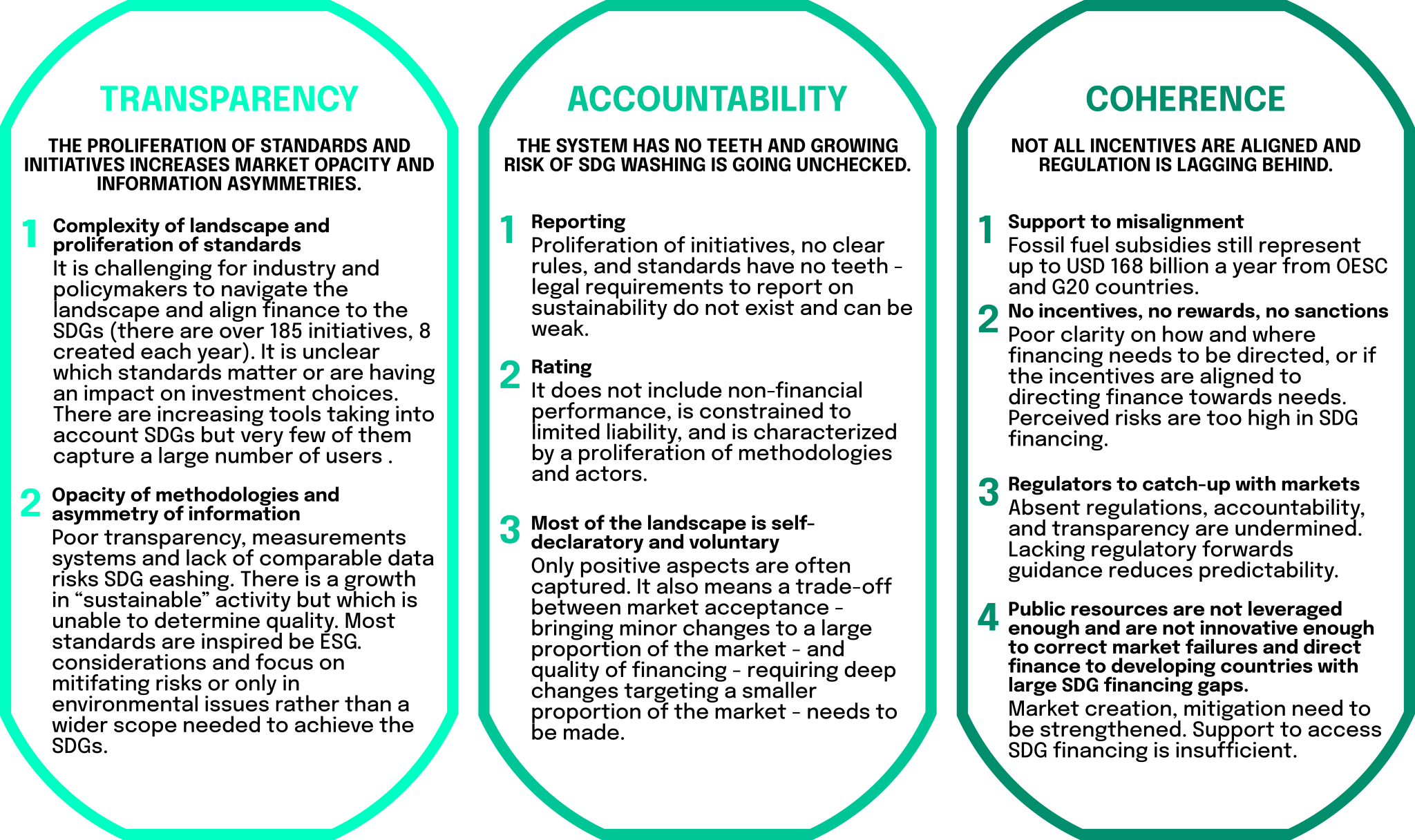

Summarizing our findings, we can identify three main issues preventing the alignment of the financial industry with the SDGs. Besides, of course the four more specific reasons mentioned above, the lack of transparency, accountability, and coherence overall play a major reason for the existence of the SDG Financing Gap. We quickly highlight the main issues of transparency, accountability, and coherence in the following graphic and introduce you to the core problems.

The role of financial institutions

Due to the urgent nature of the SDGs, the pressure from policy-makers and civil society on the business and finance sector is growing. Previously, policy-makers were mainly concerned with the environmental impact of the financial sector alone, but regulators are now expecting the financial industry to also deliver positive social and economic impacts.

Sustainable development in emerging markets requires long-term capital to finance productive investments. The international community is aware that the SDG financing gap will not be minimized, unless there is a substantial breakthrough in the search for robust sources of financing in the coming years. However, the access to long-term financing remains limited while its structure appears suboptimal due to unstable market conditions and cyclical fluctuations in the global economy. These tendencies in the global economy have had a particularly negative impact on the developing countries that do not have reliable access to international bond markets and sectors that have traditionally relied on bank lending (for example, the infrastructure sector). At the same time, the financial capacity of state budgets has also decreased in light of the recent economic crisis. Given the circumstances, the role of multilateral development banks (MDBs) has been accelerating. MDBs as financial institutions have a potential to make a significant contribution to the achievement of the SDGs. These capabilities stem from their clear mandate to support development programs, their expertise in identifying and assessing risks, as well as managing complex projects. Altogether these conditions make up for a SDG-compatible financial model that matches long-term liabilities to long-term assets.

Institutions, such as the World Bank, were originally established to fund development, growth, and prosperity, as well as to serve an exemplary role in being the earliest ESG leaders. MDBs and DFIs are particularly well-suited for SDGs funding and assisting in the transition of developing countries, due to their inherently low cost of capital and financial objectives limited to self-financing rather than profit maximization. With a broader focus on developmental and environmental goals, in 2020 the government and quasi-government institutions contributed to major investment areas that include renewable energy, green, sustainable, and social bonds, as well as education and public health infrastructure.

At the same time, even the financial framework of MDBs’ is restrained by certain constraining factors. Namely, the system’s conservative approach to lending and the relatively small equity capital of these institutions hinder the expansion of operations on a bigger scale. In light of the current circumstances of the global economy, the prospects for development appear rather unfavorable. Since the potential for direct financing from the side of those specialized financial institutions is limited, development banks began to look for alternative ways to increase investment for the implementation of the SDGs. One of such alternatives is to encourage private investment. The relevance of MDBs in mobilizing long-term financing from the private sector is primarily based on the attractive opportunity of reducing and redistributing risks.

The pandemic has had a drastic impact on the progress made towards achieving the goals of Agenda 2030. As the world has been destabilized by the coronavirus, it has further emphasized the sense of urgency in addressing global challenges related to SDGs. When tackling the challenges in closing the SDG funding gap, the role of the private sector in the context of this mission becomes more and more prevalent. While the private sector capital will be critical in dealing with the funding shortfall, those efforts will only be sufficient with collaboration based on the renewed determination and compact of all stakeholders.

With the exact purpose of enabling capital mobilization by engaging the world’s major financial institutions and industry leaders, the Capital as a Force for Good was launched in 2020. The initiative combats the funding challenge despite profound and multidimensional global change. Apart from mobilizing capital, force for Good seeks to break new ground in innovative, sustainable, and inclusive solutions in the financing sector overall.

Towards an impact ecosystem to accelerate positive impact and achieve the SDGs

So far, it should have become compellingly clear that SDG alignment can only be achieved if treated as a multi-stakeholder approach. The previous sections of the article highlighted two fundamental shifts that could accelerate the bridging of the SDG funding gap: the role of the financial sector and the shift in the norms of investing, as well as the improved forms of interaction between public and private sector to harness impact-based results. As the old stock of investments falls away, and is being replaced by a new stock built on ESG and sustainability criteria, this calls for refined business models. Those impact-based models have potential to generate new revenues, reduce costs and improve risk, while the revised impact data and metrics would help the financial sector with a holistic impact analysis.

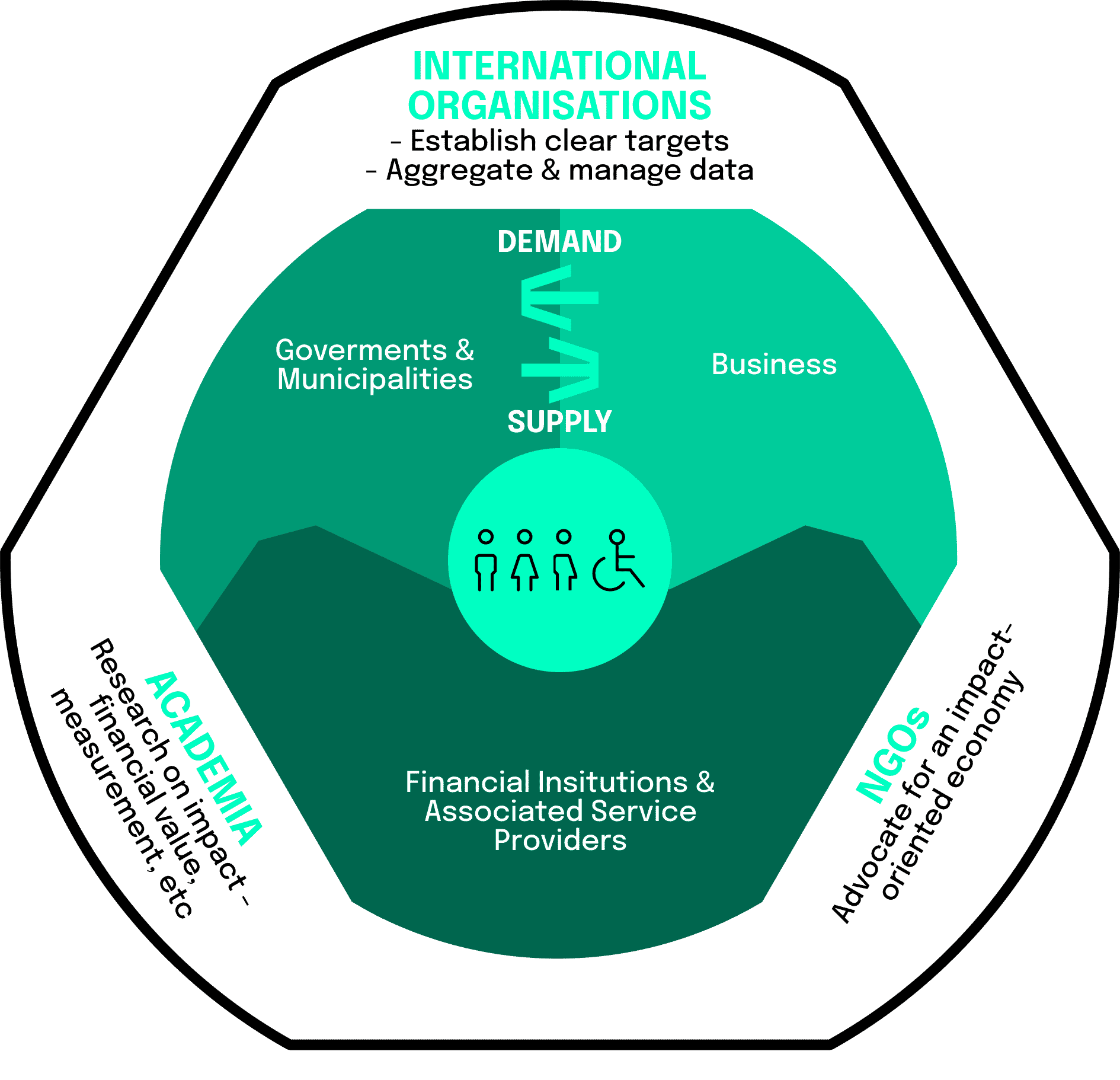

An impact ecosystem where the synergy between all the stakeholders, including private and public sector, financial sector, as well as academia, and the civil society, will contribute to the SDG challenges that cannot be solved isolated. The action plan of this model is heavily based on the unity of purpose and cooperation between all the stakeholders. To effectively guide partnership and implementation efforts, the ecosystem’s structure emphasizes consolidation of impact frameworks, organization of impact demand and supply, and revision of relevant impact metrics. The core idea of exactly this impact ecosystem is highlighted in the graphic below.

To further analyze the interconnectedness of the impact ecosystem shown by the figure above, it makes sense to take a look at some interdependencies between the sectors within it. When considering the public sector, governments and municipalities are viewed as the primary source of demand for impact. By definition, this sector should be concerned about the environmental, social and economic wellbeing of the population. Now let’s see how this sector could influence the business. As seen previously, more and more new businesses now discover the relevance of impact-based approaches. Impact is incorporated as the main growth strategy, given the ability of the evolving business-models to adapt to fast technological changes, customer demands and the potential of emerging markets. This unlocked potential creates a stake for the public sector to get involved, as the authorities have the power to stimulate the emergence and application of such business models. In return, the private sector can help the impact at a cheaper cost. Apart from being challenged to deliver solutions with the best cost-to-impact ratios, businesses will stimulate competition on impact which consequently could drive the emergence of companies focused on the integrated approaches to issues, such as energy efficiency and mobility.

Another issue that the impact ecosystem addresses is significant information and data gaps. Majority of the data related to the impact and SDGs is currently scattered across various documents, sites, and databases. International organizations and standard-setters can play an important role in collecting and managing data, all while pursuing their work in research and stakeholder convening. Once this data is aggregated and properly organized, it could effectively support the needs of various users within the public and private sectors. Moreover, as a proactive force in developing the collective understanding of impact, academia could contribute by compiling impact definitions, indicators and predictive models.

The final emphasis of the impact ecosystem falls on the civil society and NGOs. Human needs being at the heart of SDGs, individuals, and their communities represent a strong agent of impact in their demand for positive impact goods and services. As their part is mainly concerned with advocating for the emergence of the impact ecosystem, civil society’s engagement with the public and private providers also makes it the ultimate guarantor of the delivery of impacts and the integrity of business models.

As many pieces of the introduced ecosystem are being built, the rise of impact as an organizing concept for the multi-stakeholder alignment is the biggest opportunity on the road to achieving SDGs. Impact frameworks for the finance sector, public sector programs, RFPs, and impact-based models as part of refined demand and supply, as well as the improved impact metrics are all part of connecting the dots. Pandemics should be taken as a lesson showing that global challenges cannot be solved isolated, and therefore require a collective approach and commitment. Current setbacks in achieving the 17 SDGs serve as a test of the world population’s dedication to addressing those challenges and the systematic, interrelated risks that they imply. Bringing all the components together is the matter of urgency that lies at the core of the 2030 Agenda. In the following article of this series, we will focus on the innovative financial instruments and disruptive solutions that each respective sector contributes to financing sustainable development and determining whether the world can rise to the challenge of the SDGs.

Bhagat, S. (2022, March 31). An Inconvenient Truth About ESG Investing. Harvard Business Review. Retrieved June 26, 2022, from https://hbr.org/2022/03/an-inconvenient-truth-about-esg-investing

Raghunandan, Aneesh and Rajgopal, Shivaram, Do ESG Funds Make Stakeholder-Friendly Investments? (May 27, 2022). Review of Accounting Studies, forthcoming, Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3826357<>or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3826357

Uhrynuk, M., Burdulia, A. W., & Agrawal, N. (2022, January 17). Leveraging Taxonomies: How Asset Managers Are Using New Sustainability Classification Systems – Part III. Mayer Brown. Retrieved June 25, 2022, from https://www.eyeonesg.com/2022/01/leveraging-taxonomies-how-asset-managers-are-using-new-sustainability-classification-systems-part-iii/

Uhrynuk, M. (2022, March 29). ICMA Identifies Usability Challenges – and Recommends Action – for Implementing the EU Taxonomy. Eye on ESG. Retrieved June 24, 2022, from https://www.eyeonesg.com/2022/03/icma-identifies-usability-challenges-and-recommends-action-for-implementing-the-eu-taxonomy/

Johansson, E. (2021, March 30). Credit implications of brown taxonomy greater than green version. Expert Investor. Retrieved June 25, 2022, from https://expertinvestoreurope.com/credit-implications-of-brown-taxonomy-greater-than-green-version/

Nicito, A., Koloskova, K., & Saygili, M. (2019, April). Brexit: Implication for Developing Countries (UNCTAD Research Paper No. 31 (UNCTAD/SER.RP/2019/3)). UNCTAD. https://unctad.org/system/files/official-document/ser-rp-2019d3_en.pdf

UNEP FI & Société Générale. (2018, November). Rethinking Impact to Finance the SDGs (No. 978–92-807-3724–0). UNEP FI. https://www.unepfi.org/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/Rethinking-Impact-to-Finance-the-SDGs.pdf

OECD & UNDP. (2020). Framework for SDG Aligned Financ. OECD. https://www.oecd.org/development/financing-sustainable-development/Framework-for-SDG-Aligned-Finance-OECD-UNDP.pdf

Flugum, Ryan and Souther, Matthew, Stakeholder Value: A Convenient Excuse for Underperforming Managers? (August 23, 2021). Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3725828 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3725828

EFAMA. (2021, September 7). Brown taxonomy: An opportunity to transition away from significantly harmful activities | EFAMA. Retrieved June 29, 2022, from https://www.efama.org/newsroom/news/brown-taxonomy-opportunity-transition-away-significantly-harmful-activities

Robinson-Tillett, S. (2020, March 9). EU taxonomy advisors call for expansion from green to ‘brown’ in final report. Responsible Investor. Retrieved June 22, 2022, from https://www.responsible-investor.com/eu-taxonomy-advisors-call-for-expansion-to-brown-in-final-report/

Hawker, E. (2021, December 14). Taxonomy Delays Thwart EU Green Deal Momentum. ESG Investor. Retrieved June 22, 2022, from https://www.esginvestor.net/taxonomy-delays-thwart-eu-green-deal-momentum/

Alarcón, J. (2022, February 11). THE LEVERAGE OF THE TRILLIONS: The outlook on finance and investment for the SDGs. GlobalCAD. Retrieved June 27, 2022, from https://globalcad.org/en/2022/02/11/investment-for-the-sdgs/

neosfer GmbH

Eschersheimer Landstr 6

60322 Frankfurt am Main

Teil der Commerzbank Gruppe

+49 69 71 91 38 7 – 0 info@neosfer.de presse@neosfer.de bewerbung@neosfer.de