20min reading time

Status quo of financial systems and financial deployment in developing countries

Efficiency and main challenges of the banking system in Africa and Latin America

Accordingly, we would like to look at Latin America and Africa as regions whose banking infrastructure is rudimentary. Compared with the European banking structure, that in Africa, for example, is relatively shallow, simple and little penetrated. This can be illustrated by looking at a few macroeconomic indicators to understand the depth and then the behavior of the banks there.

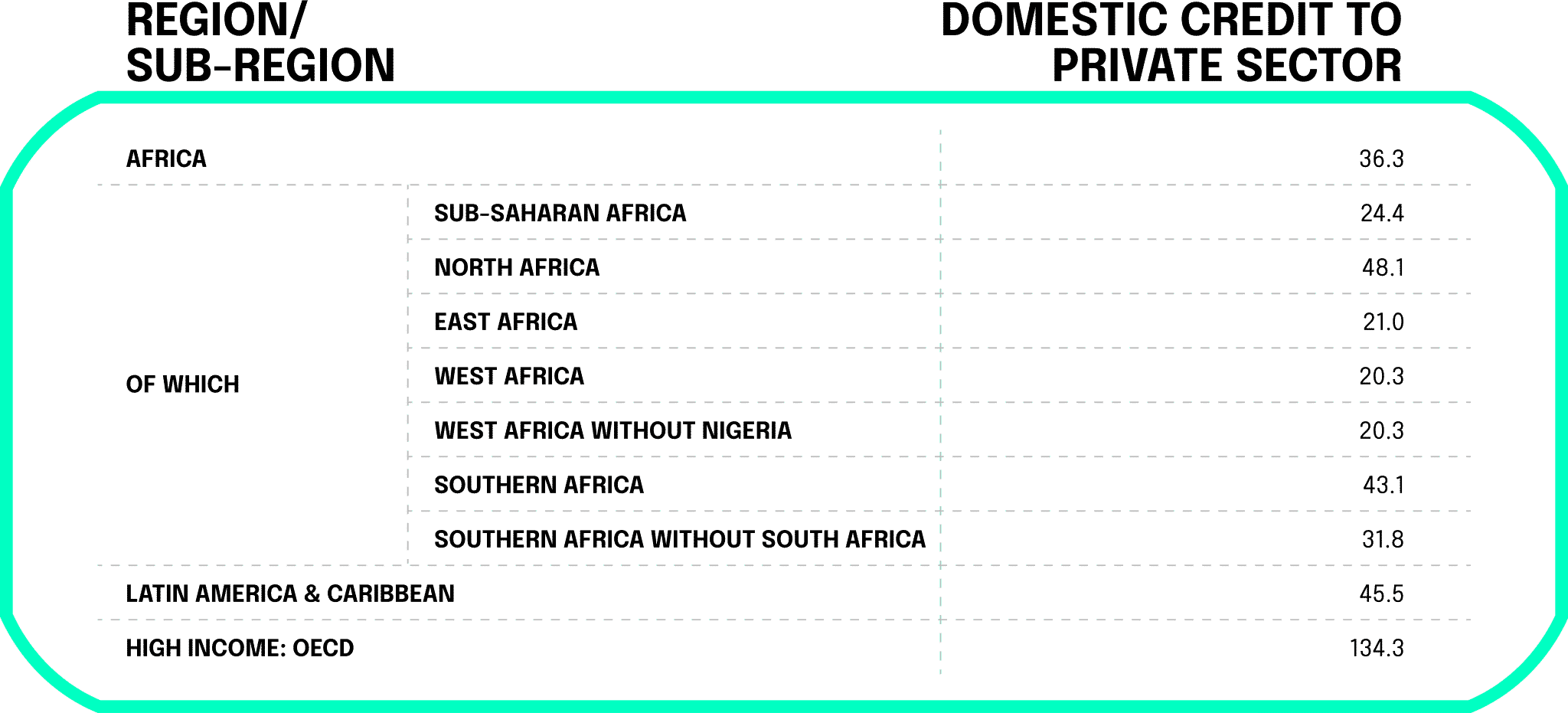

The first indicator that comes to mind is domestic credit to the private sector, expressed as a percentage of GDP (gross domestic product). This ratio is often used as a sign of financial penetration. It shows the effectiveness or efficiency of financial intermediaries in channelling investor money from the private sector. Looking at the following table, it becomes clear how large the gap is between the African (representing the AfDB (African Development Bank Group)) and Latin American continents and the OECD (Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development) countries:

Of course, this indicator must always be viewed in context, as low-income levels, total GDP, foreign direct investment and many other factors can influence these indicators. However, the core problem of the African banking system is already emerging here. In this context, the BMZ (German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development) and the World Bank have published a detailed report on Africa’s financing, focusing in particular on banks.

Although Africa is a rapidly growing economic region, the average size of an African bank (in terms of assets) is only $220 million. For a non-African bank, this figure is nearly $1 billion. This fact is relevant because it directly affects the liquidity, lending and services a bank can offer to people and the impact a bank can generate.

African banks are not only small, but besides that, they do not provide enough intermediation and intermediation services. The loan-to-deposit ratio is a commonly used metric to measure the effectiveness of a financial service provider’s intermediation. The loan-to-deposit ratio provides a reliable, approximate estimate of the effectiveness of intermediation and represents one of the main roles of financial intermediaries. This is to maximize the savings and their benefits of a society through private sector growth. According to the BMZ and World Bank Financial Report, African banking systems intermediate on average just 74 percent of their deposits, compared with 109 percent in developing countries outside Africa.

Another important finding highlighted by the AfDB is the cost that banks can incur from these assets. In Africa, operating costs are generally 5.4 percent of a bank’s total assets, compared to 1.7 percent in OECD countries. This means that banks in Africa are much more expensive to operate than banks in OECD countries. Looking specifically at West Africa, this ratio is even higher, at more than 6 percent. These costs are often passed on to the end consumer, making interaction with banks much less attractive.

In Latin America, the financial market is also underdeveloped in many areas. If we look at the ratio of credit to GDP, it does not even reach 50 percent. In the high-income OECD countries, this figure is 134.3 percent. The reasons for this are mainly structural inflexibility and high investments in digital banking infrastructure to compete with foreign providers. This in turn leads to high costs, which makes it unattractive for many residents of these countries.

In addition, many residents of these countries claim not to have enough money or do not have any identification documents with which they could legitimize themselves at the respective bank. Equally relevant are the often great distances to the nearest bank branch, and in some cases people even decide against opening a bank account for religious reasons. Despite all the inefficiencies, the Latin American banking system is one of the fastest growing in the world, according to McKinsey.

Nevertheless, there is room for improvement in many areas in Latin America, e.g., with regard to the accessibility of financial services. The trend here remains the same. Latin American countries also perform somewhat better here compared to Africa, but lag far behind the more developed OECD countries. Looking at data from 2015, 33.7 percent of citizens in Latin America and the Caribbean had a bank account. In 2020, this figure rose to 55 percent, highlighting a promising trend. In Africa, this figure averaged just 24.7 percent in 2015. Over the same period, the African continent has also been able to improve its ratios, almost reaching a figure of 50 percent in 2022

In general, only 21 percent of people in Africa have access to financial services, compared to 34 percent in Latin America (OECD average: 90 percent). However, there are promising, positive developments in Africa. In the 1980s and 1990s, several banks on the continent switched from manual banking systems to computerized front-office services. In the last decade, they have invested in systems for electronic transactions and Internet banking. This use of digital infrastructures has allowed domestic banks to compete more effectively with large foreign competitors and reach more customers. At the same time, banks have been able to increase profits through lower operating costs, although costs (at least for customers) are still exorbitantly high. The fact that digitization has already begun and countries are investing in innovative solutions provides a positive outlook for the future.

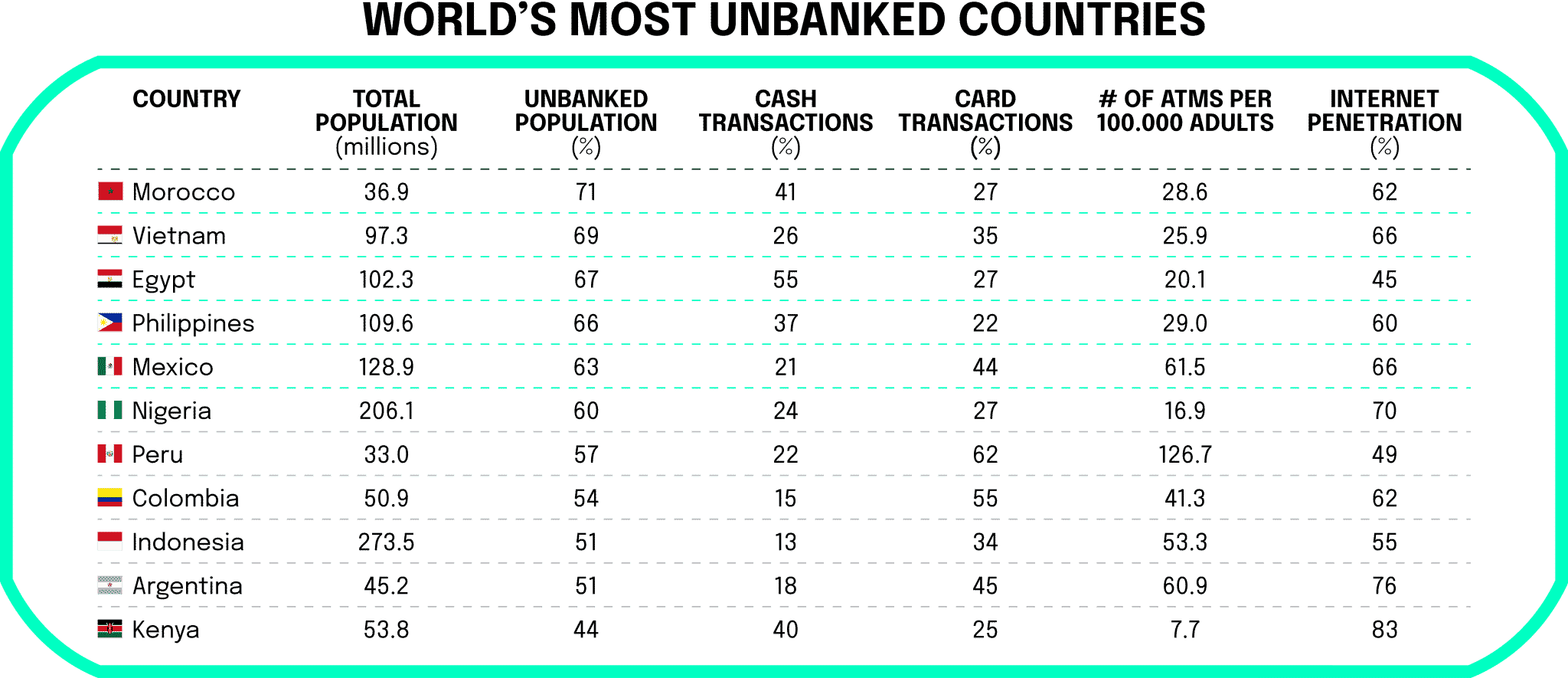

As of 2017, 1.7 billion people had no access to financial services. The largest contributors to this statistic are China (225 million adults) and India (190 million adults), according to a World Bank report. They are followed by Pakistan, Indonesia, Nigeria, Mexico and Bangladesh. The percentage of the population without access to banking services (as of 2021) is even over 60 percent in some countries. Looking at the comparatively high internet coverage, however, one may ask to what extent traditional banks are necessary at all? In some countries, a form of “leapfrogging” can already be observed. This means that few people there have ever had an account at what we would consider a “traditional” bank, but instead use services directly from digital financial service providers. We will look at two such examples in the following chapter.

Digital solutions to improve access to financial services

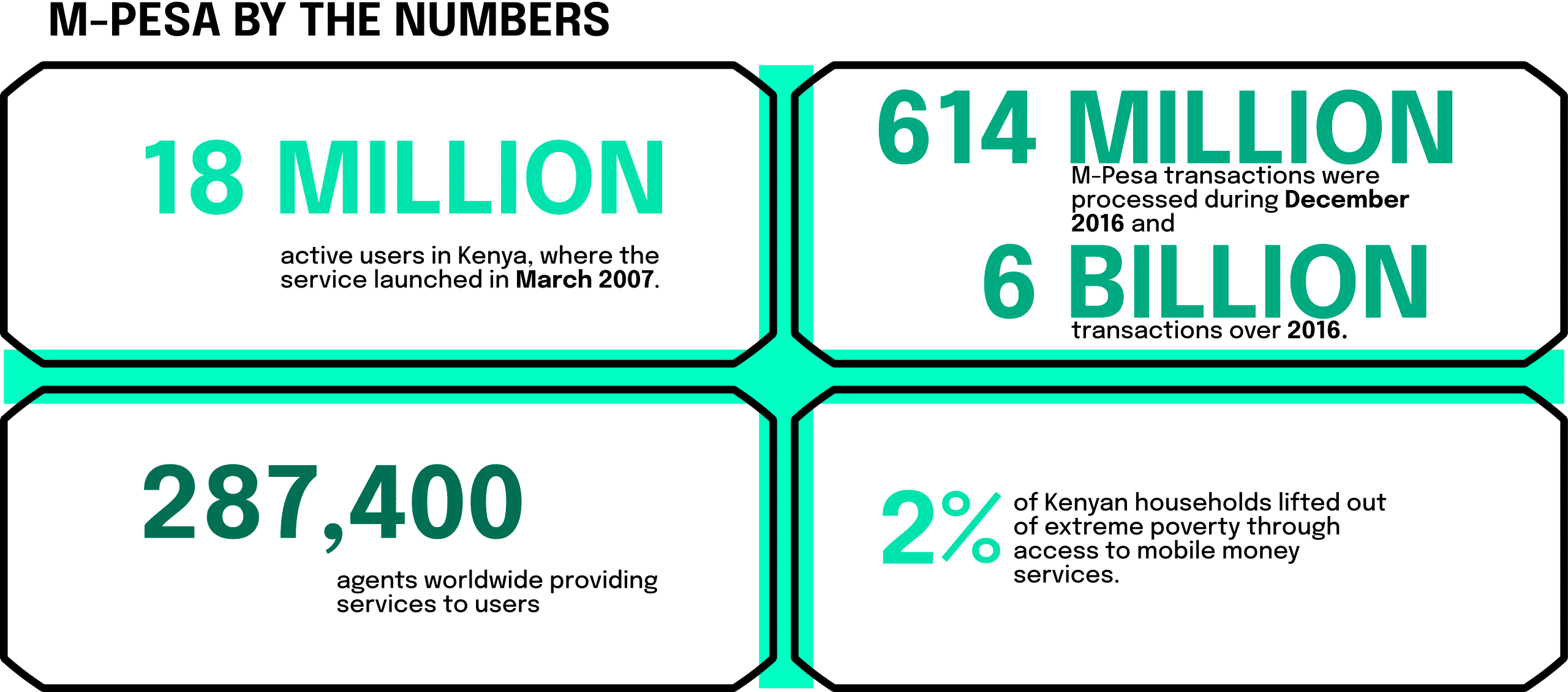

One of the best-known FinTech innovations on the African continent comes from Kenya and is called M-Pesa. It started in 2007 as an electronic money transfer service, enabling customers to save money on their cell phones. Nowadays, the scope of services has increased significantly, and even businesses can use M-Pesa to process payments. As a result, the service now reaches a total of 51 people in seven countries (Egypt, Ghana, Kenya, Lesotho, Mozambique, Tanzania and the Democratic Republic of Congo).

The introduction of M-Pesa in 2007 has fundamentally changed Kenya’s banking system. Numerous household surveys show that financial inclusion has increased significantly over the past decade. In 2006, only 18.9 percent of the population had access to regulated financial services, including banks, insurance companies, microfinance institutions, and cooperative deposit-taking institutions. By 2016, access to these services had expanded to 42.3 percent of Kenyans.

But how does the whole system work? To use M-PESA, all you need is a Safaricom cell phone and a national ID card. There is no need to go through a time-consuming registration process like at a bank, as M-PESA is much more informal than traditional banking services. Once registered for the program, one can go to the nearest M-PESA agent (a physical person) and deposit money with them. In return, one receives the virtual currency called “e-float”. The “e-float” can then be exchanged with another M-PESA customer via SMS. Alternatively, “e-float” can be exchanged from an M-PESA account for cash at an agent.

It is clear to see how Kenya has solved the problem of unbanked people using one of the most widely available technologies today, the SIM card. Users can send money to suppliers and family members via SMS, among other things. When we look at the numbers, we can really understand how great the innovation and support is for the people of Africa who previously did not have access to financial services.

In Latin America, Brazil in particular has established itself as a success story. This development is the result of restructuring the regulatory environment for payments, extensive use of technology, and a focus on developing products that benefit Brazilian citizens. Covid, in particular, has greatly accelerated the development of digital payment solutions, as in Brazil. According to the World Economic Forum, about 16 million people have gained access to Brazil’s financial system since the pandemic began, and overall, 85 percent of Brazilians now have access to financial services.

Neobank Nubank has played a major role in this development. The start-up was founded in São Paulo in 2013 and is now one of the largest digital banking platforms in the world with 53 million users. More importantly, the startup has managed to provide access to financial services to 5.6 million people who never had the opportunity to use them before. The company offers services around spending, saving, investing and lending, and also emphasizes the importance of creating shared value, ESG and social impact, which is closely related to our last chapter.

Financial inclusion and SDGs

The Digital Financial Inclusion Report of the United Nations (UN) provides a relatively good illustration of the positive effects that the adaptation of digital payments can have in relation to the 17 SDGs. In particular, the eradication of poverty (SDG 1) is of course obvious and can be achieved if more residents have access to digital financial services. As of today, 1.6 billion people (!) in the world (about 20 percent of the world’s population) are still considered “unbanked,” meaning they do not have an account with a financial institution or mobile money provider (such as M-Pesa). A positive example from Burkina Faso, for example, shows that mobile money users are three times more likely to save for unforeseen events and health emergencies than non-users of these services.

In addition, we would like to highlight two examples that relate to SDG 2 No Hunger: By digitizing its payments, a leading coffee exporter that supplies 12,000 Ugandan farmers reduced costs by 27 percent. When indirect effects (e.g., increased business productivity) are taken into account, the savings were as high as 45 percent. In addition, various digital platforms such as M-Louma (Senegal), Napanta (India) or 2KUZE (East Africa) enable smallholder farmers to sell their products directly to wholesalers. This cuts out middlemen, creates price transparency, leads to higher incomes for farmers, and helps fight hunger.

Even in terms of improved access to water and sanitation (SDG 6), positive effects come from the introduction of digital payments, as the UN report shows. For example, a Kenyan water utility was able to increase its revenues by 28 percent within 18 months. This was due to the use of digital billing and payment systems provided by software company Wonderkid. In Bangladesh, the government and the World Bank teamed up to support the installation of hygienic toilets through microcredit. This involved using mobile money to repay loans, which helped increase efficiency – 16,500 toilets were installed in 2017, with a long-term goal of reaching 170,000.

The conclusion to be drawn from the field is that digital finance and innovations can improve the living conditions in countries of the global south in a variety of ways. Anyone interested in learning how digital finance supports the SDGs not mentioned here is encouraged to read the UN report.

DeFi and blockchain innovations

DeFi - architecture and its applications

Decentralized Finance (DeFi in short) refers to all traditional financial services that are processed via a decentralized platform or blockchains. DeFi includes all financial applications that (in contrast to the traditional financial sector) are not subject to a central actor/intermediary. Unlike traditional banks, all of this is done in an automated manner via a defined blockchain protocol and smart contracts that replace all manual activities. DeFi is usually used thanks to applications called “dApps” (“decentralized apps”) and many of the popular providers are built on the Ethereum blockchain, which is the most widely used for these purposes.

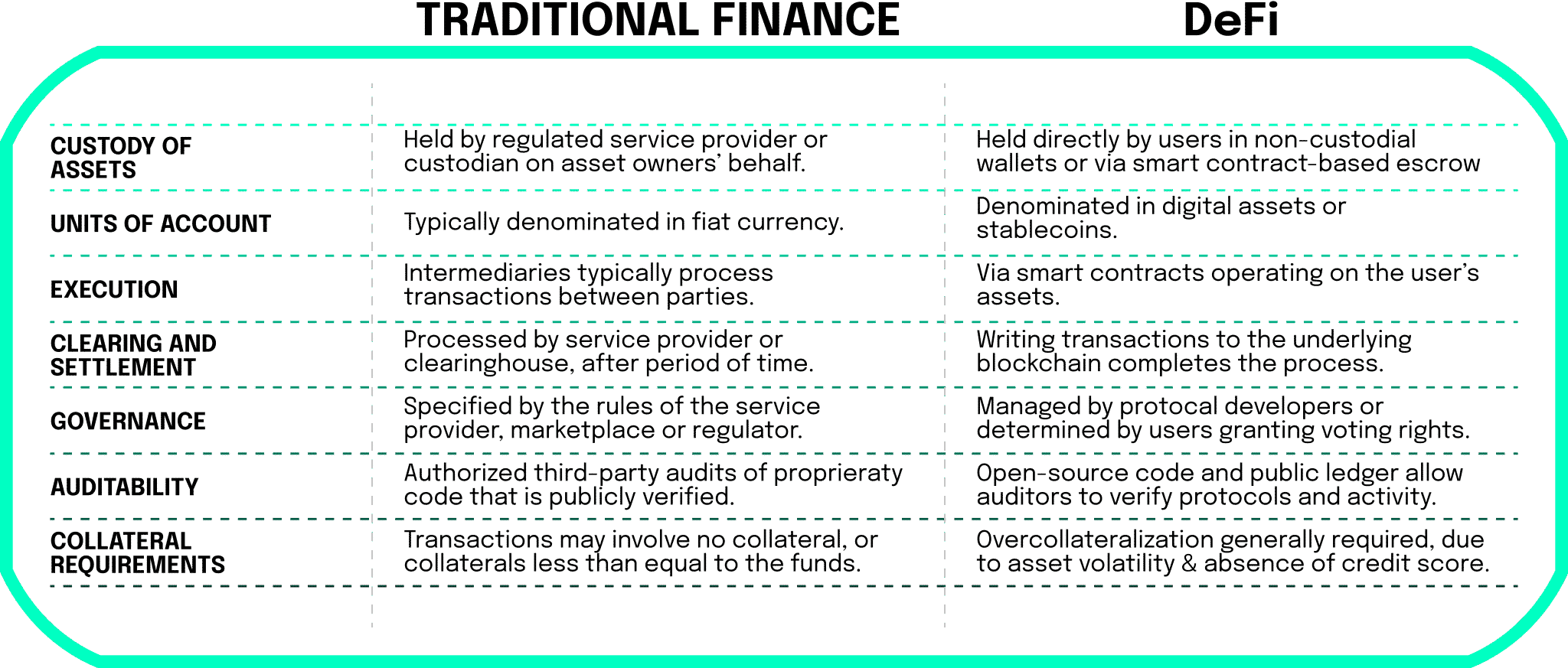

DeFi has expanded significantly since DeFi Summer 2020, before momentum then slowed again this summer. The total value (TVL) of DeFi, according to data aggregator DeFiLlama, increased from less than $1 billion two years ago to $230 billion in April 2022. To better understand the potential implications of DeFi on the structures of the traditional financial system, it is worth looking at a direct comparison between the two, shown below:

CeFi vs DeFi

Centralized Finance (CeFi) is defined as being based on the concept of a conventional currency. This is issued by a centralized entity, with the financial value of such a currency backed by the government. However, with the advent of the blockchain, DeFi has rapidly gained popularity and users. DeFi offers users most of the features we are familiar with from CeFi (e.g., the ability to exchange assets, issue loans, trade, and exchange currencies). The advantages of DeFi include the increased transparency and accessibility it offers compared to the traditional financial model.

Due to the transparency created (e.g., through open-source code), it is possible for the community to decide for itself which project to use/support. In addition, regular voting takes place by the community to decide in which direction DeFi projects should develop.

By refraining from excessive data tracking, DeFi also tries to protect private agreements. This is intended to eliminate backdoors for third-party data collection and create more transparency.

Just as the technology behind credit cards and online payments once revolutionized the digital commerce landscape, modern cryptocurrency-based banking and payments are driving the transition from the centralized fiat financial era to disruptive decentralized currency solutions. Blockchain technology is generally recognized as a secure, robust and efficient system, allowing users to trade directly with each other without relying on centrally controlled servers. By moving away from a central location or authority, decentralized systems naturally create a self-regulated environment where functions, authority, and people are dispersed. All in all, DeFi enables risk diversification of systemic risk, as decentralized systems are no longer dependent on a few intermediaries.

But why do we observe significant decentralization efforts in recent decades, especially in developing countries? Research has shown that there are numerous underlying consequences of the transition from centralization to decentralization. For example, looking at a region with such unique socioeconomic and political characteristics as the Middle East and North Africa (MENA), a link can be made between the lack of decentralization efforts and slow economic progress. MENA countries are known for having more centralized structures compared to other developing countries. This phenomenon is closely related to the historically centralized fiscal system in this region, as well as the constant threat of internal and external conflict that raises suspicions of territorial loss and government collapse. This century has seen a particular upsurge in centralization in the Middle East and North Africa, as it has been used as the main solution to prevent total collapse.

The list of problems associated with a highly centralized public administration system is extremely extensive. The literature on this topic also analyzes many effects of fiscal decentralization on economic growth. In particular, a negative correlation has been found between fiscal centralization and country size, per capita income, and the degree of democracy. So if we want to democratize precisely these countries, it is time for DeFi. But it is not only the overthrow of anti-democratic systems of government that DeFi can achieve.

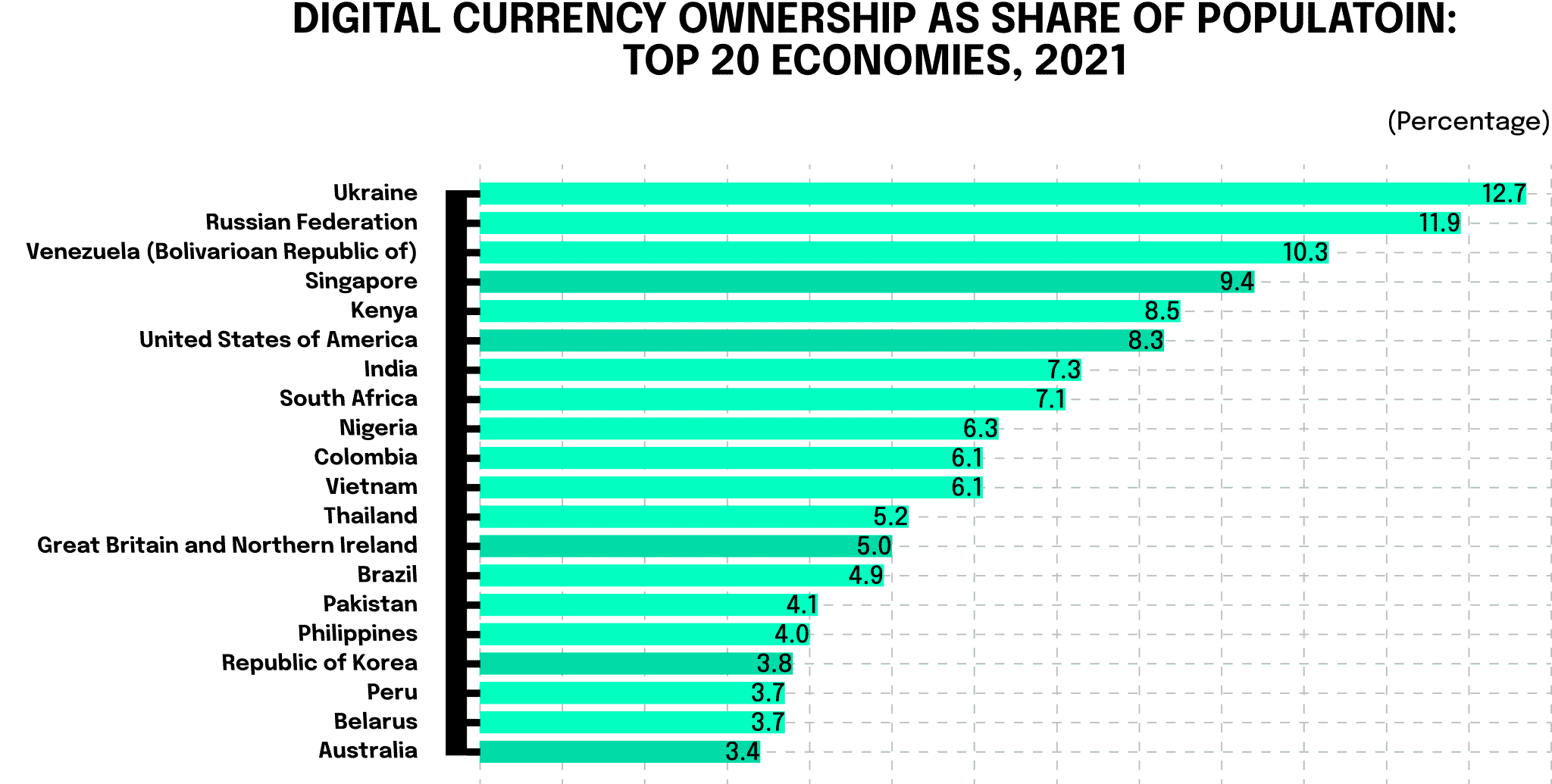

If we look at the percentage of the population that owns cryptocurrencies, we find 15 developing countries among the 20 largest economies (United Nations, see figure). Especially between September 2019 and June 2021, crypto adoption increased significantly, and mainly in developing countries. Two primary reasons were crucial for this. First, the use of cryptocurrencies is an attractive channel for remitting funds. During the pandemic, the already high cost of traditional remittance services in developing countries rose sharply once again, making holding cryptocurrencies even more attractive. Second, cryptocurrencies were used as a means of protecting savings in some countries in the global South, particularly by middle-income households. This was particularly strong in countries facing currency devaluations and rising inflation (triggered or exacerbated by the COVID-19 crisis).

DeFi - applications/forms

Before we get into what specific DeFi use cases might be relevant for residents of developing countries, we first need to learn about the most common “investment types.”

Staking

As described in the second blog article, a consensus mechanism for validating transactions is called Proof-of-Stake. Staking essentially works by owners lending their coins of a particular cryptocurrency (e.g., the new Ether, Cardano, Solana) that uses proof-of-stake to a provider (also called a staking pool, such as Lido) for a period of time. The staking pool in turn uses the borrowed coins to earn coins in turn. The more pooled capital (in the form of coins) a staking pool holds, the more likely it is to be assigned the next validation process and earn the accompanying staking rewards. The original holders of the cryptocurrencies participate in this by being rewarded in turn with interest (also called Annual Percentage Yield, APY). However, one should be careful here. In the event of insolvency, you may lose all your coins.

Lending

Another way to generate passive income is to lend crypto assets to other people (or liquidity pools) in exchange for interest. In decentralized lending, lending occurs directly on the blockchain without intermediaries (unlike P2P lending). Lenders and borrowers interact using smart contracts, autonomously and at regular intervals, which set interest rates (providers include Aave and Compound).

Yield farming

In yield farming (as a subform of lending), users contribute their cryptocurrencies as token pairs to a so-called “liquidity pool”. These liquidity providers in the Web3.0 world are comparable to “traditional” liquidity providers on the Forex market. That is, they deposit a currency pair, such as Bitcoin and Ether with the respective DeFi platform. Once the provided tokens are held in a decentralized application (DApp) through a smart contract, users receive a fee or interest in exchange for the liquidity pool being able to use the provided assets (e.g., to lend them to others). This is similar to depositing money in the account of a bank, which in turn uses the money for lending, etc., in return for which one receives a certain, variable share of interest income. Thus, yield farming helps ensure liquidity throughout the DeFi ecosystem.

Decentralized exchanges such as PancakeSwap, Uniswap, and Yearn Finance use automated market maker (AMM) algorithms to execute orders and process trading services automatically.

Liquidity Mining

In general, liquidity mining is a derivative of yield farming. In this process, the crypto owners lend their assets to a decentralized exchange and are rewarded in return. Liquidity miners are typically rewarded in the native tokens of the blockchain they use , and they also can earn governance tokens, which allows them to maximize the types of participation in a given project. As with any liquidity pool, providers are rewarded based on the amount of liquidity pool they have provided.

How can crypto and defi help developing countries?

Banking and saving the unbanked

Before we go into more detail about the potential of cryptocurrencies and DeFi in countries of the global south, we should briefly mention a use case for the general use of blockchains. For example, in the report mentioned earlier, the UN emphasizes that Africa needs blockchain technology. The reason for this, it says, is the resulting improvements in transparency, reduction in inefficiencies and falling prices in many sectors of the economy. India has emerged as a pioneer among emerging economies. There, it is showing how the adoption of blockchain can lead to significant social improvements in areas such as land titling, transparent supply chains and comprehensive health records. For example, residents inside the northeastern states of Assam and Sikkim are using blockchain technology to secure their land titles. These were originally promised to them by the government after independence in 1947.

In general, an important feature of crypto is easy access and anonymity (possibly especially important for minorities/persecuted groups in certain regions). Basically, all you require is an internet connection, a device, and a crypto wallet. After setting up the latter, I can start trading tokens/currencies via crypto exchanges. Access to DeFi services is often effortless via mobile or online wallets, where cryptocurrencies can be stashed and coins can be purchased via apps from crypto exchanges (in Nigeria, for example, KuCoin). So, in principle, all that is needed to participate in the crypto market is a cell phone and sufficiently good internet. Celo offers a well-known application in this context. The start-up is building a mobile-first blockchain platform as well as a set of financial tools that are accessible to anyone with a basic smartphone and is specifically aimed at developing countries.

This is of course of interest to market participants in developing countries who do not have any identification documents to prove their identity to banks or other institutions. Nevertheless, there is a certain risk involved. On the one hand, questionable and illegal transactions could be processed via the blockchain. On the other hand, there is a risk that a service provider might have to file for bankruptcy (as seen recently with Celsius) and lose customers’ tokens (as long as they are not stored in a separate wallet). Scams occur just as often, and alongside this, many cryptocurrencies are subject to high volatility. Indeed, contrary to many earlier statements, they are not a hedge against inflation. The DeFi ecosystem, which previously experienced extraordinary growth, recently lost only 68 percent of its total volume, which is 156 billion. U.S. dollars.

Still, it’s important to keep in mind that put in relation to rampant inflation in some developing countries, this no longer sounds so dramatic. Inflation in Zimbabwe, for example, has steadily increased since 2017, reaching as high as 557 percent in 2020. In Venezuela, inflation was reported at a staggering 65,000 percent in 2018, prompting the government to restrict the lower and upper limits on bolivar-denominated credit spending to maintain the stability of the currency. Naturally, many low-income households suffered as a result. It stands to reason that in countries like Zimbabwe and Venezuela, cryptocurrencies are quickly becoming attractive relative to unstable local currencies. To protect against the volatility of many cryptocurrencies, stablecoins are also a good option. Stablecoins are backed by a reserve asset, such as a fiat currency or a basket of currencies, cryptocurrencies or otherwise. They are intended to be stable in value, i.e., to prevent price fluctuations. A widely used stablecoin is USDC, which is supposed to represent the US dollar at a ratio of 1:1. One of the reasons for the high importance of stablecoins such as USDC, apart from the value stability, is their use for cross-border payments.

For many developing countries, migrants’ remittances are an important source of foreign earnings. In low-income countries, they are particularly critical, accounting for nearly 4 percent of GDP. In middle-income countries, this figure is about 1.5 percent of GDP. It is essential to note that remittance flows are very constant in this regard, often increasing in times of economic downturn or after a natural disaster when private capital flows in the recipient country decline. However, remittances still come at a high cost. According to UNESCO’s 2019 Global Education Monitoring Report, the average cost is 7 percent, traditional banks charge an average of 10 percent, and in some cases fees can be as high as 20 percent. Out of desperation, people pay these fees to support relatives in Africa, Asia and Latin America and contribute to their financial stability. In 2022, remittances to low- and middle-income countries are expected to increase to $630 billion (+4.2%). In 2021, the top five remittance recipient countries were India ($89 billion), Mexico ($54 billion), China ($53 billion), the Philippines ($37 billion), and Egypt ($32 billion).

DeFi greatly reduces these fees (often only the staking fees need to be paid) and saves migrants and their relatives billions of US dollars this way. Relatives back home can then use the cryptocurrencies or stablecoins to earn passive income in the form of lending or staking. Lending and staking also offer cross-country opportunities. One of the biggest promises of the blockchain revolution is a redistribution of capital across countries. Many people in developed countries have a lot of wealth and have a lot of money sitting in a bank account that is not earning interest or even paying fees to the bank. In many developing countries, it is precisely this wealth that is lacking, and microloans with exorbitantly high interest rates (50-100%) are regularly common there. Now imagine being able to offer a crypto loan directly from Germany to a person in a developing country via DeFi (in the form of lent coins). For me, the interest income would be higher than if the money is just sitting in a bank account and the borrower would have to pay lower interest than with domestic microloans. Currently, it is almost impossible to lend directly to these countries due to high fees, regulatory hurdles, language, bureaucracy. Incidentally, the risk of loan default is much lower than commonly believed: Studies show that 95 percent of all microloans are repaid.

The risks of cryptocurrencies and DeFi have already been mentioned, but the business model of the Web3.0 play-to-earn game Axie Infinity has made this particularly clear. In the Philippines, a real hype broke out, many locals saw it as a real opportunity to supplement their income (sometimes at about 80-160 US dollars per month). Good players earned up to 600 US dollars with Axie Infinity (somewhat comparable to Pokémon). However, many Filipinos learned the downside of the game. Before you can join the game, you have to buy a so-called “Axie monster”. While the hype, these became more and more expensive so that many locals either went into debt to be able to participate in the game. Or they offered themselves as players to wealthy investors from abroad. The investors then bought the starting monsters, while the locals had to invest up to six hours a day to “level up” the monsters. Most of the resulting profits went to the Investor:in. Then, however, the Axie currency stopped rising, and it became increasingly unprofitable to play. As a result, many Filipinos (sometimes highly indebted) dropped out, which led to a strong devaluation of the Axie exchange rate (the peak in November 2021 was 139€, today Axie is worth almost only one tenth).

Conclusion

Bojanic, A. N., & Collins, L. A. (2019). Differential effects of decentralization on income inequality: evidence from developed and developing countries. Empirical Economics, 60(4), 1969–2004. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00181-019-01813-2

Chen, C., An, Y., & Li, J. (2020). Research on Decentralized Trading Strategy of Electricity MarketBased on Blockchain Technology. E3S Web of Conferences, 185, 01022. https://doi.org/10.1051/e3sconf/202018501022

Chit, M. M. (2019). Financial Information Credibility, Legal Environment, and SMEs’ Access to Finance. International Journal of the Economics of Business, 26(3), 329–354. https://doi.org/10.1080/13571516.2019.1645379

Filipcic, S. (2022). Web3 & DAOs: an overview of the development and possibilities for the implementation in research and education. 2022 45th Jubilee International Convention on Information, Communication and Electronic Technology (MIPRO). https://doi.org/10.23919/mipro55190.2022.9803324

Gillpatrick, T., Boğa, S., & Aldanmaz, O. (2022). How Can Blockchain Contribute to Developing Country Economies? A Literature Review on Application Areas. ECONOMICS, 10(1), 105–128. https://doi.org/10.2478/eoik-2022-0009

Hepworth, N. (2015). Public Finance and Economic Growth in Developing Countries: Lessons from Ethiopia’s Reforms. Governance, 29(1), 149–151. https://doi.org/10.1111/gove.12185

Kshetri, N. (2022). Policy, Ethical, Social, and Environmental Considerations of Web3 and the Metaverse. IT Professional, 24(3), 4–8. https://doi.org/10.1109/mitp.2022.3178509

Mertzanis, C. (2020). Financial supervision structure, decentralized decision-making and financing constraints. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 174, 13–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jebo.2020.03.004

Momtaz, P. P. (2022). Some Very Simple Economics of Web3 and the Metaverse. SSRN Electronic Journal. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4085937

Peña Orozco, D. L., Gonzalez-Feliu, J., Rivera, L., & Mejía Ramirez, C. A. (2021). Integration maturity analysis for a small citrus producers’ supply chain in a developing country. Business Process Management Journal, 27(3), 836–867. https://doi.org/10.1108/bpmj-05-2020-0237

Schär, F. (2021). Decentralized Finance: On Blockchain- and Smart Contract-Based Financial Markets. Review, 103(2). https://doi.org/10.20955/r.103.153-74

Thornton, J., & Vasilakis, C. (2019). Do fiscal rules reduce government borrowing costs in developing countries? International Journal of Finance & Economics, 25(4), 499–510. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijfe.1771

Williams, N. J., Jaramillo, P., Taneja, J., & Ustun, T. S. (2015). Enabling private sector investment in microgrid-based rural electrification in developing countries: A review. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 52, 1268–1281. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2015.07.153

neosfer GmbH

Eschersheimer Landstr 6

60322 Frankfurt am Main

Teil der Commerzbank Gruppe

+49 69 71 91 38 7 – 0 info@neosfer.de presse@neosfer.de bewerbung@neosfer.de